Last week, on the day my latest novel was published, I did something I’ve been wanting to do for a long time: I closed my Facebook and Instagram accounts. Since I deleted my Twitter/X account over a year ago and don’t do any other social media, this means Substack is now the sole way I will be sharing my writing online. It has felt a little scary but also, already, like a very liberating kind of commitment to something exciting and real. The reason for that commitment is the support I see, every day, coming back at me from readers, and the evidence Substack has shown me about hard work and creativity being rewarded. I have put a lot into my writing here since the end of last year and in that time - mostly due to people recommending the page, or sending my essays to friends - the number of free subscribers to The Villager has almost doubled.

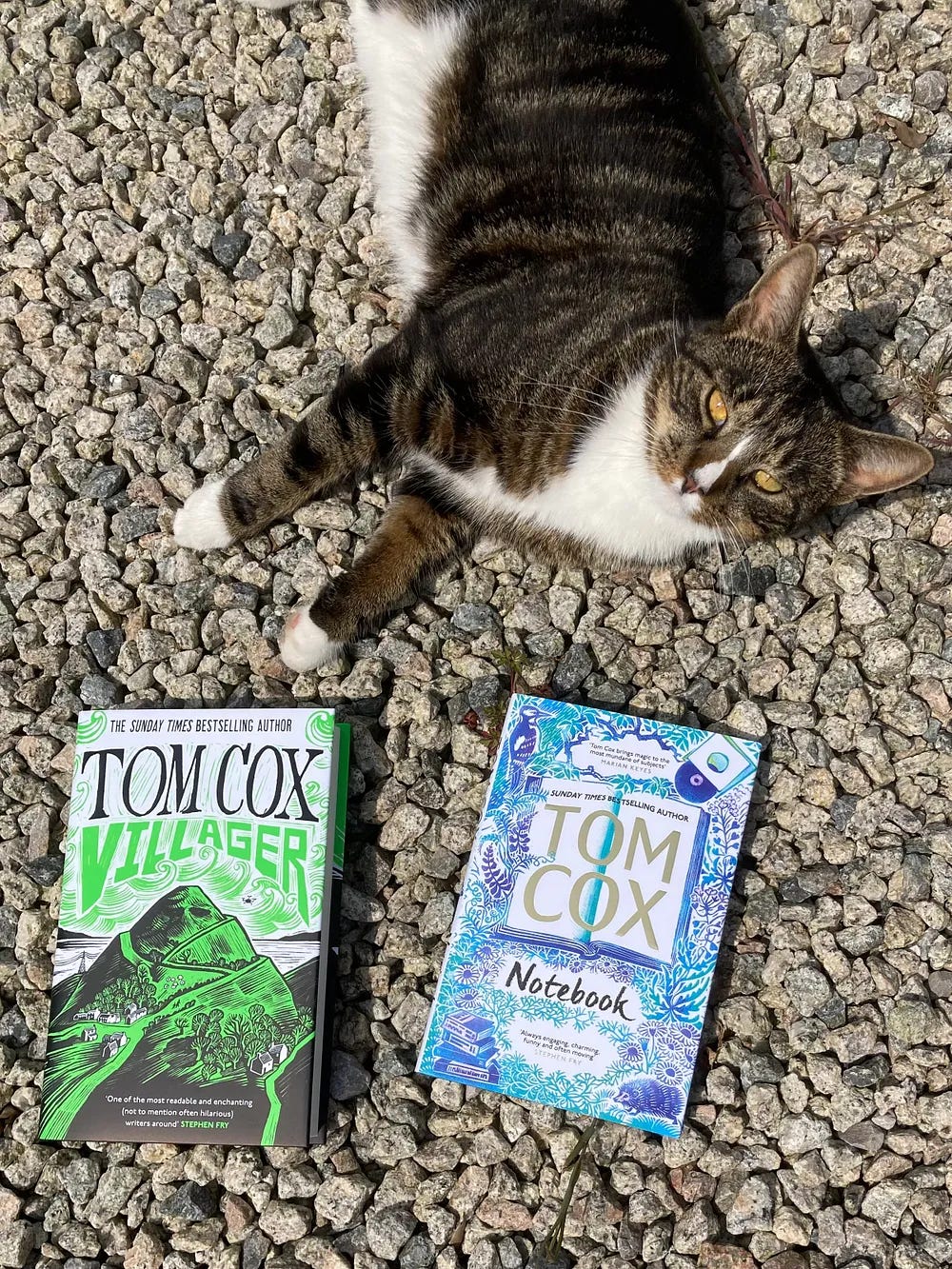

Over the last few months I have been sending these two hardback books, signed and personalised (unfortunately just by me, not Professor Charles Cardigan), to everyone who has taken out a full annual paid subscription to this page, wherever they happen to be in the world. When people subscribe, I email them for their address, then send the books, always within a day or two.

A lot of people might suggest that it doesn’t make sense, as a use of my time. The process has vacuumed countless hours from my life, involving drowning in mailers, and making constant trips to a post office 6.8 miles from my house (I live in a rural area and reaching the nearest shops means travelling down several narrow, convoluted lanes). Much as I’ve tried to train Charles to use pens and packing tape, I don’t have an assistant in any of this. Then there’s the cost of the postage (it’s around £30 to send two hardbacks to the US, Canada or Australia), replacing a few books that have gone missing (I’m now sending everything tracked, to avoid a repeat of that), the pens, the mailers, the original cost of the books themselves and the percentages that Substack and Stripe take from each subscription.

So why am I doing it?

I am not a fan of short cuts or (eugh) “life hacks”. I believe in the long game. I have huge faith in these books, which I put my heart and soul into and fought for years to make exist, and I love the thought of them reaching the hands of people who genuinely want to read them, nearby or thousands of miles away. I also love the feedback about them - and the one that’s just followed on their heels - I’ve been getting from the people who have read them.

That feedback has not yet begun to coalesce into something bigger, something which contributes more tangibly to my future security. These things take time. And who knows? it might not change anything. But I know some people love the books and I believe - since this page appears to still be growing - that one day it might change something. And if it doesn’t, it’s still a lovely feeling to know that people are reading and enjoying my work. It’s the thing that often keeps you going when trying to make a living as an author feels like banging your head repeatedly against a wall of clannish media elitism and branding-driven corporate nonsense.

When I feel confused, or hopeless, or like it’s all still a futile battle after all these years, that feedback I get from my readers feels like truth. Something powerful, indisputable and motivating.

So I have decided to carry on sending both books out to every new annual subscriber. At least until the end of summer. Probably longer. There’s no question about it in my mind: it’s worth it.

A big thank you - both from me, and from these lambs who hypnotised me into joining their cult a few weeks ago.

Tom

A HEALTHY YOMP FROM CUCKLAND VIPERS FARM TO MOGFORD SHALLOWS AND BEYOND (11.7 miles)

It is a day for walking on the margins, a time to avoid the centre of everything scrupulously. Your route takes you down a sunken path where the assorted rubble underfoot feels as untrustworthy as a plumber’s diary. You turn left down a farm track and arrive at a barn and look up at a window in the barn which has thick vertical wooden bars which put you in mind of an old prison. A farmer arrives, tells you not to look at it, and asks you what you are doing. You reply that you are here to research your novel, which is about evil farmers. He invites you in for some soup.

Soon you realise you are living at the farm. It is hoped that one day you will marry Beth, the farmer’s daughter, although you are yet to meet her. All the farm’s four fields have names: there is Thistle Field, Volatile Old Hag Field, Peter Field, Gentle Field and Brian Field. The farmer tells you he was planning to have more fields but was worried he would forget what they were called. At the rear of Peter Field, which is named after an uncle who once had a panic attack there, you hop a fence, because it seems more interesting than merely jumping it, and head down and then up a gully. Through the gaps in the hedgerows you see rusting farm machinery watching you like sad old robots staring through the windows of a disco.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Villager to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.