It’s amazing, the ways all our different minds work. We give names to some of the ways but that’s just a method of attempting to stop all our different minds from being blown by the unbridled diversity at play, all the minuscule differences that mean no person can be non-unique in how they digest the world. I have a friend who runs a record shop and has aphantasia, which as well as being a good name for the kind of jazz-tinged late psychedelic era rock band he might sell me an album by for a competitive price, means he can’t create pictures in his head. “I can’t even see boobs in my mind,” he once told me. “Never have been able to.” On the drive back west from his record shop that day I had to listen to the second Doors album, ‘Strange Days’, because since my friend had said he couldn’t see boobs in his mind I’d had Jim Morrison in my own head singing “I caaaaan’t see your boobs in my mind” to the tune of ‘I Can’t See Your Face In My Mind’. As Jim Morrison sang it, I noted that I saw Jim’s face in my mind, vividly, at its cheekboned 1967 prettiest, back when he kept himself alive solely on stolen oranges and LSD. After my friend, who is of the same generation as my parents, had told me about not being able to see boobs in his mind, his colleague asked me if I fancied a cup of tea or coffee. I told her I’d love a coffee. My friend said he would have a tea. “He’s only had four cups of coffee in his life,” said his colleague. “And I can remember all of them,” added my friend. He paused for a second, as if in deep thought. “But I can’t picture them.”

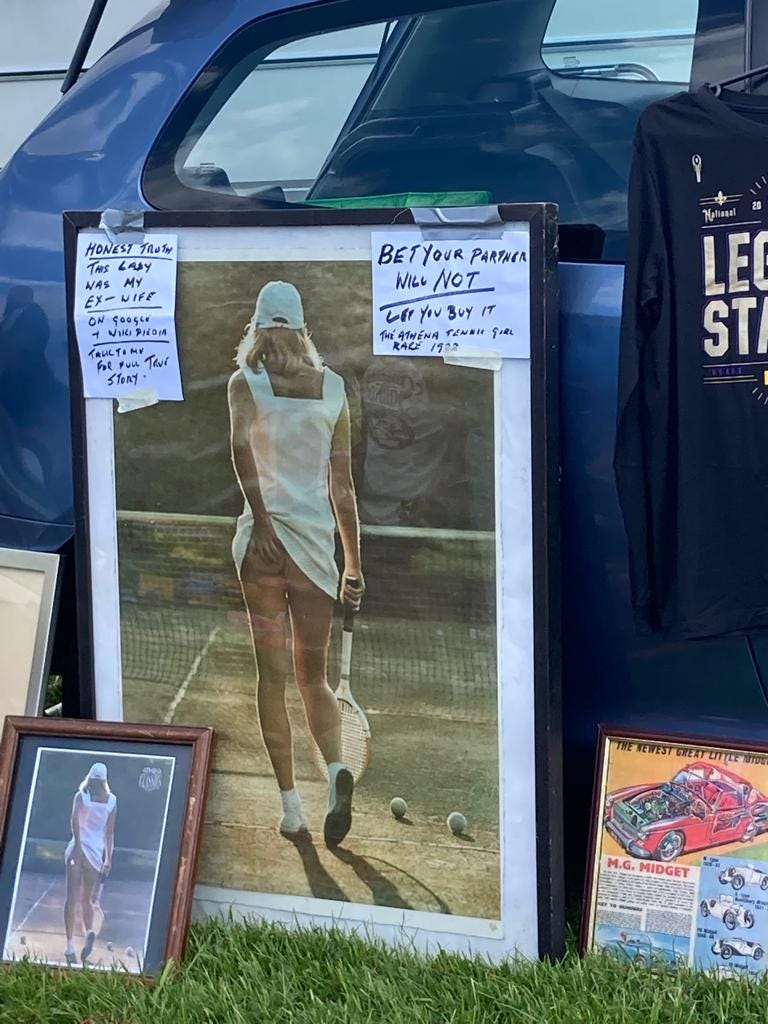

We went to a carboot sale, four friends and I, all of us with our varying hopes and requirements. I nipped off to do my own thing, tumbled through a portal in time and by the point that I was reunited with everyone, on some seats beside the chip van, everything was winding down. I nipped off again to make a man in a large hat an audacious offer for an anglepoise lamp, which he accepted, then I returned with the anglepoise lamp and we all discussed a stall we’d seen which was dominated by the famous mid-70s poster of a lady scratching her bum during a game of tennis, with a sign next to the poster written by the stallholder which said “HONEST TRUTH THIS LADY WAS MY EX-WIFE ON GOOGLE + WIKIPEDIA TALK TO ME FOR FULL TRUE STORY.” We said we should probably go back and take him up on his offer but then, maybe because it seemed greedy to try to wring too much from the day, we didn’t and I still think about it from time to time, and I know my friends from that day do too, because now it seems quite unlikely that we will ever get another chance.*

I miss going to the Victorian redbrick terrace where my mum and dad’s friend Jean lived, in central Nottingham. It always smelt great, there was a Tunisian rug on the living room wall and the next-door neighbour’s unflappable cat Posy was often there, helping out. I think the last time must have been Jean’s 50th birthday, 1998 or maybe late 1997. My uncle Tony was there and asked me how much I was earning. Jean still read the Beano every week, just as she always had. Sheep loved her, even though she was never less than thoroughly rattled by them. One day, when we were all on holiday in a cottage in the Forest Of Bowland, she and her then husband Pete went for what they intended to be a long walk along the gruelling ridge of moorland above the cottage, through the snow, only to return no more than twenty minutes later, pursued by a flock of enthusiastic Herdwicks. It was viciously cold, just like it always was when we went on holidays in the northern counties in February, and the owner of the cottage refused to let us use the house’s full range of heating appliances. Four of the Herdwicks followed Jean all the way into the kitchen. While she escaped to the safety of an upstairs room the rest of us stood in front of the Rayburn, stroking and admiring the sheep before gently escorting them back out into the weather. Later my uncle Tony got his toolbox out and made the heating come on properly.

I dropped my girlfriend off at work and drove to Taunton. I didn’t have any particular reason to, but it felt ok. There were poppies on the building sites and people in the secondhand shops were talking about fights they’d seen recently. I noticed my hands were still stained with Araldite from trying to fix an old lampshade the day before. I got home and we went for a drink at David and Steve’s, down the lane. They showed us the part of their garden where they’d planted Hellebores over a part-submerged 1960s car, so now they were two of those people you sometimes get who have a vehicle-shaped Hellebore sculpture in their garden. They told us about their friend Sean whose partner had trained his parakeet to say “Sean’s a puff!”, which had meant that, when he’d been on holiday and his mum had been looking after his house, his parakeet had come out on his behalf. Back at home, we realised our other neighbour had finally moved out and that she and her boyfriend had run over our tomato plant in her boyfriend’s van, stuck to which were stickers showing a comedy ticklist of other things they had run over, including a rabbit and a person in a wheelchair. Actually, no. That was a different day. The tomato plant was still there at this point, as was the van, with its comedy ticklist of things our neighbour’s boyfriend had run over, including a rabbit and a person in a wheelchair.

I need to be better with my notes. I’ve got a note in my latest notebook, from several months ago which says “You underestimated my crevice” and another next to it that says “Bring a skull home if it does not morbidly afflict you.” I don’t know who said either or why I wrote them and as the days go on that increasingly strikes me as a shame. On the following page is another note that says “We are enlightened but fucked.” Quite near that there’s another note which says “extensive wankland of smug fakery”. I remember what the fourth note was about and where I’d just been when I wrote it but I’m not telling you because my life is a small campaign against potential misunderstandings.

One of the most haunting things that happened to me last year was when an old dog ran out of the night directly at my friend Ben Tallamy’s car. At the time Ben was driving very carefully around the bend where the old dog always hung out, half a mile up the hill from the house where I then lived. Dogs get old but, because of all the fur and everything, until you see them moving they can often look very much like the dog they once were, but you could tell this dog was old old, even before he moved, which he usually didn’t. All day, every day, he sat on that half-blind bend, across the road from the pub, watching the cars edge through the space beside him. When I passed in my own car, I always did so very slowly, opened the window and addressed the dog by his name and enquired about his health. I asked his owner, who lived at the farm across the road, if she worried about him getting hit by one of the less careful drivers who were on the increase in the area. “Nah,” she said. “We call what he does ‘Traffic calming’.” I trusted what she said since he was her dog and, from what I could gather, he had been there since around 1978, and hadn’t got hurt so far. Which is what made it even more surprising when he reared up out of nowhere, red-eyed, in front of Ben’s headlights. Had Ben not been a steady and conscientious driver, the dog would likely not have survived. All four of us who were in the car felt shaken afterwards, troubled by the wild look in the old collie’s pupils. It was as if we had experienced an uncanny visitation firsthand: seen one of Dartmoor’s many ghosts take full possession of their chosen subject and turned him briefly into something he was not, some essence of the place’s dark ancient heart. We decided that a drink was definitely in order. As I remember it, I was buying, since I was feeling bad for breaking the passenger door handle on Ben’s car the previous week by accidentally pulling it too hard.

Some walks you remember so much more clearly than others. Maybe there was nothing especially remarkable about them, you were just more in the walk that day, in your head. The stepping stone walk was one for me: five sets of them, 13 miles, all on one tiny grudging winter’s day. My safe, relatively nonchalant negotiation of one set still blows my mind, a couple of years later: all nine of the stones were totally submerged, yet I made it over, with ease, light and balletic in my movements, instantly ready to take it on again, if anyone had asked, which they didn’t, because nobody was there; they were all in their houses, being sensible and normal and warm. It was that time of year on the moor when you get to know the trees better and see all their bright green feet, witness the vast lichenous disarray of the place in full. The battery on birdsong has finally run down to nothing and it feels like your soul has been wired up to its variations all along. The walk started as pure lockdown winter survival, with a bit of exercise thrown in for good measure, but became something better. I remember the sign on the church near the point where I decided my route would begin: “What does God want for Christmas? Look in the mirror!” I didn’t have a mirror, so I looked in the church window, where my stained reflection greeted me. “God wants a £6 teal anorak from his local Heart Foundation shop?” I asked out loud. But I did have new walking boots: the most expensive ones I’d ever bought. I put my unappealing arrogance with the stepping stones at least partly down to that. I felt like one part dancing queen, three parts bag of old bones. Fortunately, the dancing part was situated where it really mattered. Later, I dropped my debit card in a peat bog. I had to go back, retrace my steps. By the time I found it, three quarters of an hour later, I had written four or five decent pages of novel in my head. It was one of those days when a lot of what’s bad is really good, including the rain. By the time I drove home it had really started minging it down, or to be more accurate, minging it sideways, pushed by a wind from somewhere even higher and more forsaken that I didn’t want to be. Several moorland ponies were sheltering behind a wall, in a line. Some waterlogged sheep had snuck in on the very end of the line, hoping nobody would notice they were sheep. But I was there, and I noticed. I noticed they were sheep.