Edwin Starr's Redemptive Jellyfish Journey And How It Helped Him Learn To Be A Person Again

The big mistake people who’ve never had writer’s block usually make in their assumptions about writer's block is thinking that it must be about having no ideas. In truth, it’s nearly always about having too many. I’m not struck down with a case of it at the moment, touch wood, but when I have been in the past my problem has tended to be the tyrannical choice of dishes the creative part of my brain likes to serve up to the eager, industrious part. Too many stories I ache to write. Too little life to write them in. “Which is the correct path? Oh my god what if the path I am leaning towards turns out, too late, to be the wrong one?” Not so long ago, these were the questions I used to ask myself on such occasions. They’ve not precisely vanished, but my definition of “correct” has changed lately… perhaps my whole belief in “correct”. A benefit of getting older as an author is the necessity of coming to peace with the fact that you’re not going to write all the books your ambulatory mind has assured you that you need to write. That acceptance can give you a push to face the fear that the path you’re setting out on might not be that lone “correct” one but go ahead and commit hard, regardless. If there is a question to be asked now before I choose one project out of many potentials, it is less “Which of these ideas seems most artistically sound in theory?” and more “Which of these alternate universes I want to create - all of which are unlikely to be perfect - is going to be the most fun one to live inside for the next portion of my limited time on earth?”

I flick back through my notebooks and see stories I keenly desired to write but didn’t: sometimes because I didn’t think the process would be enough fun or enough of a challenge, but sometimes probably just because I got distracted and forgot. Maybe I got asked for a lift by a friend at the last minute or abruptly remembered it was Bin Day. Maybe another, bolshier idea edged the original idea out. I notice some notes from late 2018 for a story called Cafe In My Bag, about a guy who finds a reputable and fully solvent cafe in his favourite shoulder bag. I’m probably going to have another stab at that soon. I remember also, not because of a note in a notebook, but because of the heatwave the UK is currently experiencing, a story I wanted to write a few years ago, examining the idea that the scariest time of all to see a ghost would not be on a dark winter’s day but in midsummer heat, under a cloudless sky.

Now would not be the least appropriate time to write such a story. There has been something so raw and elemental about the past week’s weather here in the Devon countryside that it has seemed lightly suffused with the supernatural. I feel, at times, like I’m experiencing the flipside of the full-on spooky metereological experience I had in the winter of 2017-18 when I lived hundreds of feet above the snow line in the Peak District during the Beast From The East. As I opened my laptop to begin writing this piece yesterday a pair of roe deer hurdled the garden fence and belted past the kitchen window. Their appearance felt inimitably connected to the heat, to a particular surreal wildness in the air. A grasshopper rests on the 1987 Virago edition of Enid Bagnold’s 1938 novel The Squire, drawn in, perhaps, by the cover, which is far more grass-coloured than the grass outside. Wood pigeons are doped out of their tiny minds on tantric tree sex and, during the night, the foxes let rip with their copulatory war cries in a new, unhinged register that makes me leap out of a dream and race outside to check that one or more of our cats isn’t being disembowelled.

On Friday, as I swam in the sea, a fleet of jellyfish fired up their decentralized nervous systems and moved in from the south until they had me completely surrounded. Fortunately they were Moon jellyfish, the pacifists of jellyworld, and I was going at a gentle pace, so when I accidentally ploughed into three or four them there were no casualties. I thought, as I always do when I see jellyfish, about the person who called them “essentially little more than organised water” although frustratingly I can’t presently remember or find out who that was. I also thought about the Welsh and Gaelic Irish names for them, which translate respectively as “sea c***” and “seal snot”, and about the camp Italian man who came to this same beach with me and my friends seven summers ago and picked one of this kind up, which was how I learned they don’t sting.

I was supposed to just be swimming and reading this week, taking a break, not thinking about stories, but they keep coming, and who am I to complain. The jellyfish beach has a little unofficial nudist section at the far end, full of deeply tanned old people. I keep well away, and stick to my partially dressed middle-aged person patch, but I want to know who they are, what they do when we’re not experiencing a heatwave, because it is hard to imagine them anywhere else than here, on this beach, doing anything except being naked and deeply tanned. Do they live at the far end of the beach full-time, perhaps, in caves where they pupate during the cooler months? That’s a story, for sure. Edwin Starr, the soul singer, he’s another one. Not a nudist. A story. I have been listening to Edwin’s music a lot lately, just as I did during the summer the camp Italian man picked up the moon jellyfish, when I first began thinking about the lives of the über-tanned naked old people. That was also the summer I inadvertently melted Edwin’s 1971 Involved album by leaving it too close to a big window on a hot day. I am older now and know more about heat. Not much, but more. You could argue I even learned a fraction extra this week, in addition to learning some other less anticipated stuff, including that in Hungarian the term for grasshopper translates as “a tube that escapes”.

Bafflingly, my instinct when the weather is this hot hasn’t always been to spend every possible waking moment submerged in saltwater. Back in my adolescence, on days that were searingly hot, and on days that weren't, I played golf. That I made this choice, especially as the child of arty, working class parents who didn’t like golf, remains fogged in a certain amount of mystery, but playing the game where I did was freakishly cheap, back then, and I’m supposing I must have liked it. In my defence, at that point I lived about as far from the sea as it’s possible to as a resident of the United Kingdom.

I initially played golf on a pitch’n’putt course, in an unremarkable place just outside Nottingham called Bramcote, and then more regularly on a full-size course, about a mile away from that, in a bigger but similarly unremarkable place called Beeston, and occasionally on another course, in a place called Chilwell, less than ten minutes’ bike ride from there. What amazes me now, even more than my decision to play golf, is that during that whole period of my life, the pop star within easiest geographical reach of me was Edwin Starr, the Nashville-born singer best known for such hits as War and Agent Double-0-Soul. Starr (birth name: Charles Edwin Hatcher) lived in Detroit during the height of his fame but in 1983 made the curious decision to relocate to Chilwell, and subsequently Bramcote, where he died of a heart attack, in his bath, in 2003. Maybe my friends and I even passed him on the dogshit-flecked public footpath which bisected the rectangle of pernickety quasi countryside where we arrogantly frittered away the indolent, squabbling, thrilling days we assumed were limitless? Perhaps Starr noticed us and thought, “Oh man, look at these sad little golf dudes with their stupid clothes.” What I certainly wouldn’t have thought, if I’d seen him, was, “I wonder if this middle-aged black man who’s just walked past us carrying his shopping back from the Co-op held the number one slot in the Billboard singles chart for much of August and September 1970.”

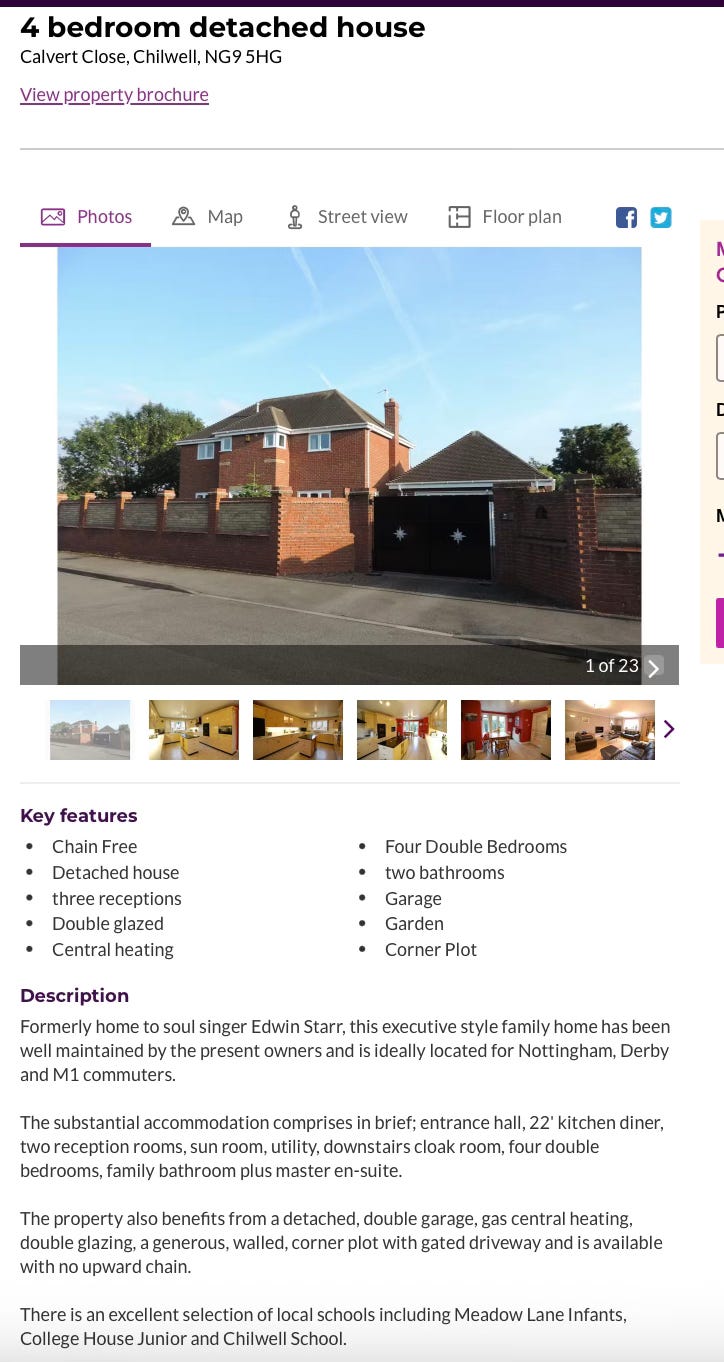

I even found a recent listing for Edwin’s old house in Chilwell, which, as you can see, is, amongst other pluses, ideally located for Nottingham, Derby, M1 motorway commuters and the esteemed Meadow Lane Infant School:

In the summers of 1990 and 1991, the zenith of my golfing fugue, I spent every moment I could at Beeston Fields Golf Club. For me the prospect of not hitting balls with a glorified stick, every moment of every day, had become tantamount to torture: my own weird redefinition of teenage angst. I turned up for my GCSE exams in body but not in mind and spirit and failed half of them accordingly. My golf mates and I tried to show each other how little golf mattered to us, yet contradicted ourselves by being there, at the golf course, every day, and on a deeper level we competed fiercely to outdo each other, experimenting with new swings, new putting strokes, new clubs, old clubs. I was the kid with the brown bread in his packed lunch, the factory reject clothes, the outmoded gear, but when I turned up one day and started chipping with a wooden-shafted 7-iron made just prior to World War One, the sarcasm of my peers turned swiftly to curiosity and a fad for jumble sale putters and chipping irons ensued. Our competitive desire to experiment, playfully, drove us on, put some of us, incongruously, in the county team and big tournaments on an international scale. In that way we perhaps had not so absurdly little in common with the musical innovators of 20 years earlier as might have seemed immediately apparent. If you were a musician in your prime at the dark end of the 60s - the part of the 60s that became numerically the 70s but was still really the 60s - you’d write and record one of the best songs ever, a song that simultaneously defined an era and sounded like it had been beamed direct from a more thrilling future, and, when the record was barely back from the pressing plant, one of your peers would have already outdone you with their cover version of it. Hendrix’s psychedelicising of Dylan’s All Along The Watchtower, The French Fries’ transportation of Sly & The Family Stone’s Dance To The Music to outer-space, Spanky Wilson’s funky drum-break elevation of Cream’s Sunshine Of Your Love. If I named even half of the full list of examples, this piece would be reduced to the status of a listicle. You see the theme come up in book after book about the 60s music scene: the laid-back grooviness as a thin varnish concealing the competition and cross-fertilisation, the frantic need to be wilder, further out, more transcendental than your rivals.

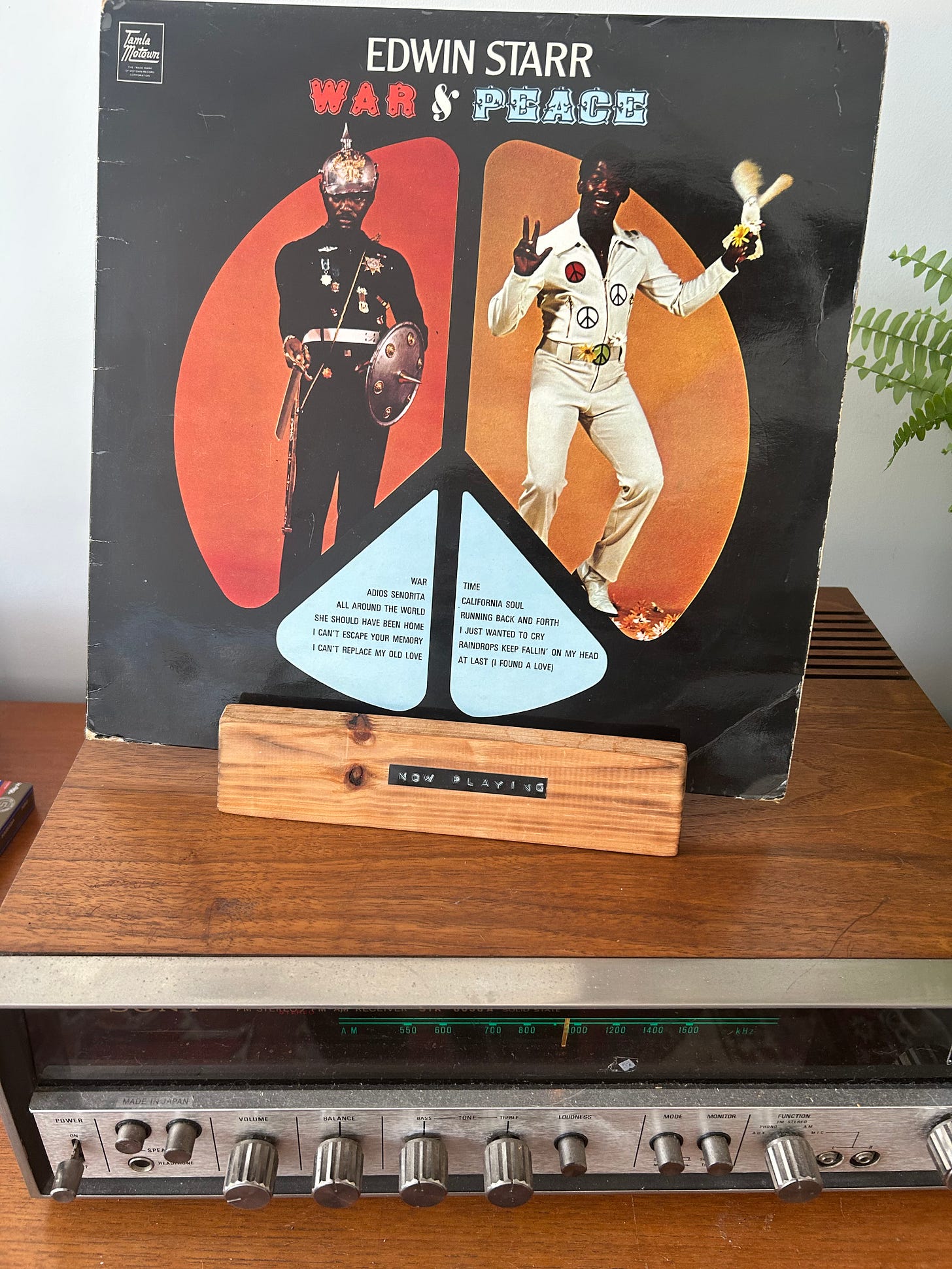

The Temptations wrote and recorded War first, for their Psychedelic Shack LP, released in March 1970. It’s hard to pick fault with their version, which is a perfect example of lysergic sunshine soul, but their label, Motown, decided not to release it as a single, fearing it was too political and would harm the band’s status as Motown’s most commercially bankable male group. Edwin Starr’s chart-topping rendition, recorded two months later, punched with a fatter, sweatier fist: it did the seemingly impossible and made The Temptations’ original sound featherweight. It came out of the speakers instantly indignant, commanding, high on its own danceable rage. For the cover of the accompanying LP, War & Peace, Edwin dressed in two contrasting outfits: a cream jumpsuit stencilled with peace symbols, and the uniform of a soldier from some jumbled era of thrift store battle. In photograph one, he scowls, holding a sword and shield. In the other, he grins, flashing a peace symbol with his right hand, while a flapping dove sits on his left.

I purchased my copy of War & Peace probably only a decade or so ago. But the first Edwin LP I got hold of was his previous effort, 25 Miles, in 2000. That ferociously hot metropolitan summer, my friend Al and I would dance to its title track most Saturday nights at a fabulous club night called Blow-Up. I didn’t know who the song was by and was too embarrassed to admit it to Al or anyone else but I scoured the record shops of London until I found a record called 25 Miles which seemed to be of the right sort of vintage, having one of those cool double exposure face-on-landscape covers that were so in vogue around 1969. “Edwin Starr!” I thought. “Didn’t my dad once tell me he lived in Beeston?” By then, I no longer played golf, but one afternoon around then, in the sun, on a patch of grass beneath Alexandra Palace, where some of my favourite musicians, but sadly not Edwin Starr, had partaken in the 14 Hour Technicolor Dream concert in 1967, I wrote the first, clunky paragraphs of a novel about the high jinx of a gang of teenagers at a golf club in Nottinghamshire. I decided to call it Nice Jumper.

“Tom is not interested in this subject because he ‘wants to be a golfer’,” wrote my Biology teacher on my final year report card, in the summer of 1991. “However, it is unfair of him to distract others.” A couple of years after I left school I had become embarrassed by my delusion that I’d had what it took to become a pro at my favourite sport, more baffled, with every passing month, at my decision to have put so much into it and so little into traditional teenage boy pursuits such as meeting girls, going to gigs and getting blind drunk. The big surprise to me, in view of that, was that my ambition to become a professional writer did not turn out to be another mockable, overambitious hallucination. By my 24th birthday I’d been given the job of Head Music Critic at a national newspaper. By 26 I had a bolshy literary agent, full of big promises, and had signed a deal for my first book with a large commercial publishing house. The self-delusion, still there but milder, was not in the fact that either of these things could happen to me but in the lifestyle, financial security and quality of work that I expected to accompany them. I wrote a decent book (for my age), then listened to the wrong people and wrote an awful book which not so much as a ventricle of my heart was in. Got dropped by my publisher, went with other publishers. Wrote some other books with some good bits in them, some much better than others, but which still weren’t the books I ultimately wanted to write. I always had ideas - sometimes a paralysing number of them - but had not yet learned that an idea in itself is not enough. Trust, experience, instinct and a willing to disobey count for far more than an idea. But you have to learn that through the prickly mess of life. I did, anyway. It probably wasn’t anyone’s fault. It’s just the way stuff happened and I see why, now, looking back from here, at all the complex coordinates around it.

In the rehearsal room, after conversations with my then agent and prospective editors, Nice Jumper mutated from autobiographical fiction to memoir. There were two reasons for this: the one I acknowledged and the one I hid from. Of course it had to be non-fiction: the fact that I was this young strip of hair and flappy-trousered dancing legs who’d also had this dark past as an unlikely golfer, was, to a publisher, at that point, my USP. But also I did not have the intellectual and emotional tools to write the kind of fiction I wanted to write and would surely have failed humiliatingly if I’d continued my attempt to. As I said, it’s a half-decent book, considering I was about six when I wrote it. Its problem was that I was still too chronologically close to its subject matter (I was barely half a decade out of my teens when I wrote those first sentences outside Ally Pally) and that I was laying the jokes on too thick, trying too hard to embellish and rearrange (my favourite freshly read book at the time was Unreliable Memoirs by Clive James) into something a little more momentous, more pop and filmy, more “Look! This is a book! This is what I think books do!”, not able yet to see many of the elements that were truly funny or interesting about my adolescence and its topography, hadn’t yet found out that, for me, when it comes to non-fiction, writing honestly about exactly what happened is the most rewarding method of all. Also, if I was going to alter a few of the characters, change their names, change the name of the golf club - all of which I did - why didn’t I give Edwin Starr a role in it too? Now, huh, good GOD, that would have been truly interesting. But timid, glad, grateful mid-20s me would never have been so bold. Would perhaps not have seen what it was good for.

The years between Nice Jumper and now are the years of me gradually seeing the places where I grew up through clearer eyes. That also means they’re the years where the fact that Edwin Starr chose to live in one of those places has gradually become more remarkable, more comical. You’d get it too, if you came from Nottingham, the most unglamorous and middling of all unglamorous middle places, a city whose musical heritage amounts barely to a battle of bands gig in a decaying garage under the shared ownership of its neighbours Sheffield and Birmingham. I have a great affection for my home city in many ways, but musicians, traditionally, don’t move to it. They move away from it. If celebrities live there, it’s generally in the private estate The Park, behind the Castle, which isn’t even a real castle. It’s not in Chilwell. Or Bramcote. And those famous people are not Motown superstars, looking for a quiet life. With every year I go on enjoying the music of Edwin Starr and every year I go on developing a better understanding of the cultural climate of my own past, I wish more avidly to learn about his post-disco life, a couple of miles from Barton In Fabis. I want to know who he hung out with, where he went out to drink, where he got his car fixed. I can’t help regularly imagining conversations he had in his daily life.

Mechanic: “All right Charles, m’duck. We’ll try to have it ready for Tuesday morning if we can get t’new tyres over from Alfreton in time.”

Edwin: “Peace, brother. But if you could get her back with me for Monday evening, that would suit me a whoooole sweet bundle more. Your man’s gotta a concert in Belper on Tuesday. Big, biiiig night, my friend.”

Mechanic: “Ooh, are you some kind of singer?”

Edwin: “You bet your ass I am, my man.”

Mechanic: “Would I have heard anything you’ve done?”

Edwin: “Well, does this sound familiar? COME ON FEET, START MOVING. GOT TO GET ME THERE. HEY, HEY. UH-HUH, HUH, HUH, OH.”

Mechanic: “Can’t honestly say it does, m’duck.”

Edwin: “Ok. What about this? So many pretty girls walkin’ down the street, and they’re sharp from their head to their feet.“

Mechanic: “T’in’t ringin’ any bells, I’m ‘fraid.”

Edwin (sighing): “Ok…. WAR! Huh (good God)! What is it GOOD FOR? Absolutely NOTHING. SAY IT AGAIN!”

Mechanic: “You know what? I bloomin’ do know that one. Well I’ll be licked by me antie’s toy poodle. So Charles int even your real name! You’re that Smokey Robinson bloke, int ya? Can you do that other one, the one from that film wi’ Charlie Sheen in it? Now take a goooooood look at my face, you’ll see my smile seems out of place…”

Has anybody done a cover version of their own book? I’ve often thought I’d like to do that with Nice Jumper. Tell a quieter, realer story, with the wider field of vision I now possess when I look at young me and the people and places I used to know. Psychedelize it a bit, perhaps, 1970-style. But what I see now is a potentially better book than that: a book that I’d find far more potentially rewarding to write. Fiction. A tender story of an teen golf outsider, a lover of the music of 1960s black America who feels slightly out of place at school and amongst the golfing crowd he bunks school to mix with, who strikes up an unlikely friendship with a politically-orientated funk musician from Detroit who has chosen the humdrum heartlands of the United Kingdom’s Midlands as the location for his reclusive retirement. Not the kind of book that would be easy to pitch to a publisher but that’s ok, because I don’t write those any more - actively avoid them, in fact. A book I would not have been capable of writing at 25 (or 35, for that matter). A book whose conclusion or most significant events I could not predict and which would be worth writing primarily because of that and because I looked forward so much to finding out what they were.

Will that be the next book, the one inspired by Edwin Starr and my misspent sports nerd adolescence? Or will it be the second short story collection I keep threatening to publish, which I now realise, to my surprise, is fairly close to completion? Will it be the novel I had to abandon in the dying months of last year when my ex-publishers upended my life by deciding to deny me the earnings they owed me? Will it be a novel that emerges, mystically, out of a sentence I wrote on Friday about a fleet of moon jellyfish? Or another, which springs from a page of notes I made on the same day about the feeling of the hot air in my garden, as a goose flew overhead, while imagining the life of a 125-year-old woman in similar environs? There are always ideas, jostling me, but I examine them with looser hands than I once did. There’s a relinquishing of something a bit like control. For me, a feature of being an obedient young author, overawed by my position and the educated air of the people shepherding my books into the world, but keen to please, was wanting some kind of reassurance that the story I was about to embark upon would work well and end well, and that my paymasters would be able to see it did before it was underway.

But, let’s face it: Where is the fun and mystery in that?

“Ok, but what’s the journey?” prospective publishers, and my first literary agent, used to ask me when I pitched ideas to them during the early part of this century. It would reliably make me cringe. But I took a while before I snapped and rebelled against it, decided to write books that were the antithesis of pre-planned “journey” books and realised that was in fact what I’d wanted to do all along.

Edwin Starr patently had no idea of the “journey” when he sang his best songs. He’s always feeling his way in: you can hear it. He’s all flex, grunt, confidence and instinct. He might have walked 25 miles but all he really knew about his route is that it would be hell on his feet and his baby would be waiting at the end of it with her loving and a kissing to make him go stone wild. His records are far from flawless, as are those by pretty much all of my favourite musicians. My favourite writers? That’s muddier water. I know there are authors whose output is without public missteps, but I’ll never be in their club. I relinquished my potential for a blemish-free backlist when I wrote a memoir too early and listened too hard to people who had other ideas about what I was and should be, listened to people who told me I needed to be Stuart Maconie or Danny Wallace or Nick Hornby, when I wanted to be EL Doctorow and really all along was just Tom and could never be anything else. But similarly, I suspect that was the way it was always going to go, the way it had to be, to get me to the point, somewhere between 2013 and 2016, where I could start to say “Ok, this is finally looking something like me.” And there’s an unexpected liberation in coming to terms with the flaws and the missteps: “Let’s do this, and if it doesn’t work out, who cares? Stuff hasn’t worked out before, at times, and you’ve come back from that.”

Nobody knows anything about what will work. Some of them will tell you they do. But they don’t.

Instinct and trust and self belief will sometimes help, though. That said, instinct and trust and self belief don’t generally appear by magic. They need to be earned.

Also, doing as much as you can to not make everything an absolute ball-ache probably won’t hurt.

I write, these days, for much the same reasons I read: to learn, and to surprise myself. For just a brief moment, a few days ago, I thought I would write a different kind of blog post to this: one with some thoughts about a scandal around a book everyone has been talking about lately. But then I realised more than enough people were already talking about it, and that I didn’t actually want to do that, and that I’m not here to get clicks via a zeitgeist-feeding headline on a piece people will part-read. So instead I started with some loose thoughts about jellyfish and Edwin Starr and thought I’d see what happened. But that book that everyone’s been talking about, the redemptive one about the couple walking the coastal path, is not wholly irrelevant here. I haven’t read it and have never had any desire to, so I can’t comment on its quality, but what I do know is that, as a mere premise, it’s precisely the kind of book that so many publishers want authors to write, the kind I have felt industry pressure to come up with in the past: the bankable non-fiction excursion, the journey book. Maybe there’s a place for that kind of book, and most likely that place will remain, despite the allegations made in The Observer newpaper the Sunday before last. But some of us are just not cut out to write it. The mere idea of something like it, the pressure coming down on us to create it, out of a life much less neatly foldable than that, can be a suffocating force. I sympathise with anyone dealing with that pressure. Because I felt it for a long time until I turned away from it and realised why I decided to write books in the first place, and that it had pretty much zero connection to the kind of rewards that particular pressure tends to promise.

There’s no sure bet, when it comes to writing books. Not for me. Not for most of us. You can’t ride and and steer this beast to safety before you’ve unlocked the cage. It’s frightening, and it’s meant to be, and if it suddenly wasn’t, you’d mourn the time when it used to be. But it also might be a source of solace to remember a fact easily overlooked: if you know what you want, and you’re doing this for the right reasons, and especially if you’ve been doing it for a while, you’ve also been training your brain in certain matters of storytelling. There’s a care and fusspottery that becomes in-built without you having to constantly tell yourself “Take care!” or “Keep the fusspottery constant!” You can probably trust, whichever path you chose of the many that dazzled you with their promise, that some submerged part of you will be doing the best it can not to make the one you have chosen a thoroughly shit one.

But, even taking that as a given, you can also take as a given that some people are going to hate it. That’s good, though: it’s what helps make the psychic sweetspot where you commune with your true readers sweeter. Embracing it is part of being a human creating what you’re obsessively driven to create. It’s part of not being AI. It’s part of not submitting to everything that’s currently trying to reduce us all to one collective exhausted, quivering mass on the cool-toned plastic floor.

Sometimes, when I’m beginning a book, I feel a strange kind of 25 again. Not the 25 I once was. But some other one I never could have been, from some other dimension. It’s one of the times I feel lucky to write books, right now, in this particular world, which nicely counterbalances all the times I don’t. And there have been a few of those, too, recently.

“Ok, yes, that’s all very well, but what’s the journey?”

I don’t fucking know yet. And for me, that’s the whole point.

In autumn last year, my then publishers, Unbound, ceased paying the money they owed to their authors, including me. Subsequently, I instructed them not to publish my latest novel, Everything Will Swallow You, took back the rights to that and the six other books I’d written for Unbound, and signed up with a new publisher, Swift Press. Unbound then went into administration. It’s been a difficult time, and has required huge reserves of patience, but I’m happy to say that the paperback of my previous novel 1983 will be published on August 14th, followed by the hardback of Everything Will Swallow You on September 11th. Both of these can be ordered from Blackwell’s, with free international shipping, and I will be signing all pre-orders of EWSY that they send out. Massive thanks to anyone who has pre-ordered, or plans to, as this really helps the book get into shops.

If you’d like to support my writing for less than the sub fee here on Substack - and save me giving ten percent of my earnings to Substack - you can do so here via my website, either with a monthly payment or a one-off donation.

The one time I saw Edwin Starr live was at a one day festival in summer 1984 in the shadow of Clitheroe Castle. Edwin wasn’t even the headline act, which was my then-favourite band Climax Blues Band, who were in the process of imploding and had already lost two key members. Weirdly, there was no publicity whatsoever for this festival, and we only heard about it on local radio the morning of the event. It seemed strange to haul a US soul star to the north west of England and not tell anyone. But a rumour abounded that Edwin Starr had actually moved to England, so his commute pre- and post-gig wouldn’t be quite as long. No one really believed it, though. It was a rumour in the same mould as the one that insisted that the cool bald guy from Hot Chocolate lived on a 1970s housing estate in Wigan. That turned out to be false, so I’m glad to hear that Edwin Starr really WAS a resident of a working class town. He and his band were excellent live, by the way.

Edwin! Here in the West Mids, everyone will tell you that he lived in Wolverhampton. Maybe he did for a while before swapping the West Mids for the East Mids? Or maybe the West Mids wanted to claim him (even though Wolvers already had Slade, ffs).

I saw one of his gigs in the late 90s at the Que Club in Birmingham - a cavernous red-brick old Methodist hall. He was AMAZING. He played "War" and everbody. Lost. Their. Shit. Brilliant! Apparently he was a staple at a lot of the Northern Soul nights.

Oh, and Blow Up - I did go once, and it was really cool. But I had trouble staying awake because I'd gone out the night before with my friend in Colchester and we had to wait for two hours for a taxi, then I woke up really early the next morning thanks to bedroom curtains that were about as light-defeating as a Kleenex. I was so bloody tired!

And... You should definitely write that ghost story! They are far creepier on a summer's day, and I once had a very odd MR James-like experience on a very hot, sunny day. I visited my mum one summer and decided to walk across the parched fields to a church to look at the headstones. On the way, I had to pass by the charred, skeletal remains of a burnt-out tree. I went round the churchyard and saw an interesting headstone dedicated to two young men killed there by a sudden bolt of lightning one summer in the 1800s. At some point, I suddenly got the feeling that *something* was following me. I could see a dark shadow from the corner of my eye. How could there be a shadow in the middle of a scorching summer day? I headed back to my mum's, heading past the charred tree, and could still feel it following me. In the end, I decided to ignore it and told myself that my grandad, who had been a Methodist lay preacher with a fascination for Borley Rectory, would look after me.

I didn't tell my mum about it. The next morning she asked me, "Did someone follow you home from the churchyard yesterday? Only this morning, I went into the lounge and had a feeling there was some there, staring at the patio doors like they wanted to go outside. So I opened the doors and the feeling went away."

What. The. Heck.