These days, when I’m writing a book, I want to learn, I don’t want to rest too hard on anything overfamiliar, I want to challenge myself to take my writing somewhere it hasn’t gone in the past, and I want a sense of the unknown: a feeling that I’m at least in part writing the book to find out what the book is about. I think about all these things much more than I did back in my 20s and 30s, when the main point of writing a book was to publish a book. There’s another consideration, too, when starting out on a new project, which seems more crucial than it ever has been: Is this book going to be a fun place for me to hang out for a fairly lengthy chunk of my life? Late last autumn I wrote a few thousand words of a new novel. The words were fairly decent, made actual sense and everything and even included a few things which felt pleasantly new, but they did not strike me as the beginning of a universe I thought would be fun to hang out in. I binned them, started again, and found a slightly tilted version of the same universe, and I’m enjoying being there a lot. Will the book be better than my previous one, Villager? I would like it to be, but I enjoyed writing Villager enormously and think the main point is that this follow-up is pulling me along in the same, addictive way where I can’t get enough of it, can’t wait to watch more of the universe unfurl. It is something new and strange beginning to exist that didn’t exist before and could not exist in the same way if it was done by anyone else and that is arguably the best and most important feeling available to any creative person. I need that feeling, every time I write, and I trust the results it will yield.

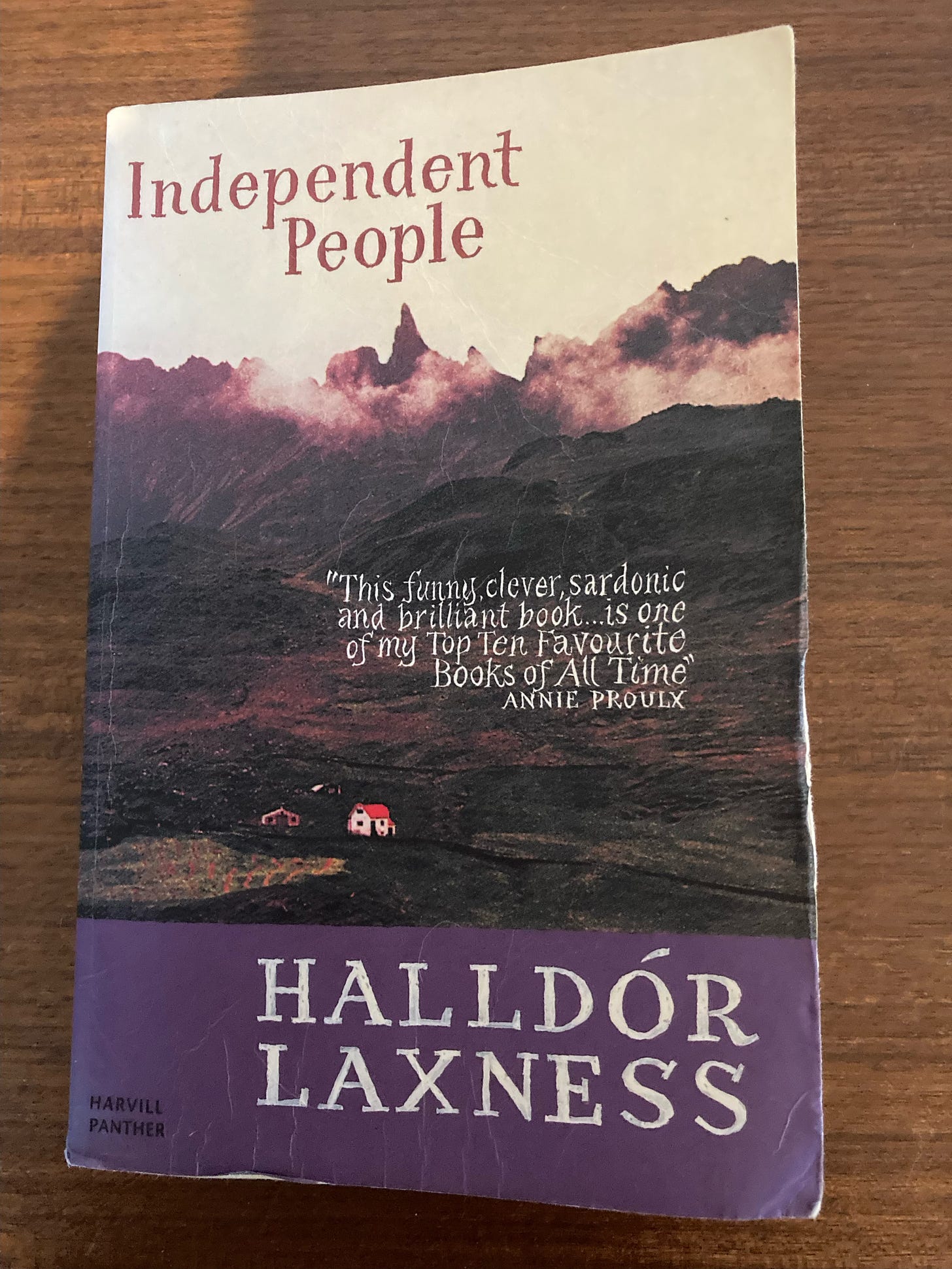

I notice that a lot of the novels I’ve read that have stayed with me most intensely - Adam Thorpe’s Ulverton is one that springs instantly to mind - were novels I took a couple, or even several, runs at before I got into them. It’s been the same with Independent People, the epic book the Icelandic writer Halldór Laxness published in two volumes in 1934 and 1935. I started it a couple of years ago, gave up, started it again, got a little further, gave up again. I’m well beyond halfway in my third attempt at it but even now, finding myself needing to come up for air and break off to read, say, a short Italo Calvino novel for light relief. Laxness is a brilliant writer: poetic, constantly surprising, unflinching as he stares at the best and worst of human nature. But it’s January, it’s been raining for twelve years without stopping here in Cornwall, I’ve just submitted my tax return and sometimes reading long descriptions of the death of farm animals in a bitterly cold Icelandic valley haunted by the angry bones of a vengeful frost hag is not the best remedy. Also, the main character is, for all his single-minded determination to make his own way as a crofter in a bleak spot without the help of the ruling class, a total git: obnoxious, woman-hating, contrary, at times breathtakingly cruel. I’ll come back to Independent People soon, no doubt be glad I persevered, owing to the way it broadened my perspective on history and the world and the things prose can do, but for now I need to listen to some high energy songs, read about outer space, buy a houseplant that I don’t have room for, go on a long walk, remind myself that life is not just one miserable struggle against the northern elements, surrounded by bereaved cattle and sheep blighted by lungworm.

Every horror writer will tell you they’re not a horror writer, so take from this what you will, but I’m not a horror writer. The Shirley Jackson Horror Writing Award I won a few years ago for the opening story in my book Help The Witch is misleading: the story is undoubtedly a creepy, unsettling one, but I doubt it would do anything for someone who solely read horror genre fiction. It’s also - in my opinion - only the eighth or ninth best story in the book, one of the ones I challenged myself least with (and undermined slightly by writing - in my subsequent book Ring The Hill - a superior, non-fiction account of the events which inspired it). There’s also a cap on the horror and terror that the other stories contain, primarily for the reason that I am a bit of a wimp, when it comes to that kind of thing, especially as I get older. The graphic violence in the films Midsommar and - especially - Hereditary was too much for me and I can no longer watch Inside Number 9 now it’s become that bit more claustrophobically dark. I think I am more liable to go to sad or scary places in my writing than I once was, because I’m more committed to covering the full range of human experience than I used to be, but I have limits, and it’s that choice again: Am I in a place I really want to hang out? I’m very happy to spend time in some woodland with a lingering ambience of terrible events that took place there 530 years ago but if there’s also a severed ear on the ground nearby I’ll probably give it a miss.

I am more than a little obsessed with the jazz musician Dave Brubeck’s former woodland home in Connecticut, built for him by his architect friend Beverley Thorne in the early 1960s. I’d take out the carpets and maybe change the sofa for the brown corduroy one I got in the Dunelm sale in 2019 but other than that it’s just about perfect: such a bright and green wedding of indoors and out, such a sophisticated party of high quality wood and stone. Brubeck was lucky enough to live in another amazing Thorne building directly before this, the cantilevered Heartwood House in Oakland, California. The TV host Ed Sullivan was so fascinated with it he decided to film an episode of his show there in 1960.

They say that the sound on singles is much bigger and fatter than on LPs. I was very inclined to believe that, when ‘Think I Care’, the bafflingly commercially unsuccessful 1968 single by the Canadian band The Paupers, exploded out of my stereo, one recent evening just after I’d finally tracked down a 45prm original of it. It’s a song that perhaps doesn’t have everything but makes you feel, for its three minute duration, that psychedelic bongos, deranged snarling vocals, sassy backing vocals and fuzz guitar actually are everything, and you could never want anything more.

Jim is an enormous, extremely soppy cat who also sometimes goes by his original name Mango and in theory lives semi-wild at a farm a couple of fields away from our house, but our cat Charles brought him over for dinner on December 6th and Jim hasn’t properly left since. Our infamously despotic other cat Roscoe is very accepting of him. Charles, meanwhle, patently falls a little more in love with him every day. During the early mornings, Charles and Jim playfight, with Charles sitting on the 1970s swivel chair in the living room and Jim spinning him in circles from below with epic paw control. Jim, who is around a foot taller than me when he stands up on his hind legs, could effortlessly deck Charles if he wanted to, but his nature is so gentle that he is always well within himself during their tussles. His immense size seems to be one of the countless things he is unaware of, along with the names of the world’s capital cities, the fact that the catflap works in the same way from both sides and the vacuum cleaner’s total lack of personal vendetta against him.

Please note that if you haven’t read Villager yet, I have a few signed first edition hardbacks here, to sell direct to people in the UK. Drop me an email for info on how to order. If you are outside the UK, Blackwells will send it to you with free delivery. Or if you would like to wait for the paperback, that will be along in late March.

I sometimes forget that in a pre-smartphone age most people didn’t take a lot of photos of their everyday life. My family did, and I am thankful for that, especially as I get further into the researching and writing of a novel set in the early 1980s in the mining country of north west Nottinghamshire, where I grew up. As I go through my mum and dad’s old albums, I fall down holes in time and little cupboard doors that have been closed for years creak open, revealing more about the way my life once was: innate events that are part of me but nonetheless seem revelatory as they return. The photo above might not seem like anything very special, but it’s one I keep coming back to. I am conscious of a lot of the reasons I like it but not all of them, and I think that makes me like it even more. It was taken by my mum in early February 1983 and I doubt she would have imagined anyone looking at it 40 years later and pondering its meaning of significance. My dad was driving, my mum was in the passenger seat, and I was in the back. The car in front of us is a mid 70s Opel Kadett C estate which contains my mum and dad’s friends Malcolm and Cheryl and their very young daughter, Rachel. It was early in the morning and - at Malcolm’s insistence - we were on the way to the cave near Knaresborough where Ursula Southeil, more commonly known as Mother Shipton, the most famous prophetess of the Tudor period, was born during a violent thunderstorm in 1488. You can see from the snowdrifts at the side of the road just how cold it is. At the time we staying in a white cottage high on a hill in Dentdale, just over the border from Yorkshire into Cumbria. The cottage had cold York flagstone floors and Breakfast TV and TV-Am had just started broadcasting. One day we drove north and walked over the border, just so I could touch Scotland for the first time, but most of the time we did very little, because my dad had flu. He sweated copiously, as a result of the illness, and his sweat froze, leaving the bedsheets covered in icicles.

There are a few more of my family photos from the early 80s - with some accompanying stories - below this line, including one of me attacking Margaret Thatcher. They will appear in full on www.tom-cox.com in a week’s time, where everyone can read them for free, but if you can’t wait until then you can always upgrade your substack to a paid subscription now.