People sometimes ask me to write more frequently about music and, particularly, to recommend obscure nuggets from my own record collection. Something that makes me hesitate about doing the latter is perhaps the historical period in which I was formed, which was a murky time in terms of information about non-mainstream music when, as a result, information about non-mainstream music was assigned a different kind of value to the one it is now. Because of that, I sometimes carry around with me a feeling of tastemaking redundancy, as if I am some MK1 robot, made partly out of oak and designed to store a few hundred neglected transcendental songs, hobbling about in an era of all-metal robots with around one million times my brain capacity. “This is so so good,” I picture myself enthusing to the other robots, as I hand them ‘Take It And Smile’, the sole album by the California band Eve, from 1970. “I found it for £18 at the little record fair at Doncaster Market a few months ago. The cover of ‘Hello LA, Bye-Bye Birmingham’ is a first rate country soul banger.” “Ok but do you not have Spotify?” the other robots reply, and I reply that, yes, I have, and sometimes even use it, although to find myself within 40 miles of Doncaster and discover there is a record fair on in Doncaster and then not spontaneously drive to that record fair in the hope that there is a record like ‘Take It And Smile’ by Eve available for £18 would require drastic modification of my original programming: a lengthy procedure involving critical risks to my central circuit box with no final guarantee of success.

“Beyond pure selfish listening pleasure, what is the wider purpose of the approximate 2500 albums and 900 singles in my house: this collection so extensively hunted down, pruned - sometimes sensibly, sometimes rashly - shaped, loved for so many years, which - now more than ever - has its own unique personality, containing multitudes but can ultimately almost all be accessed digitally, by anyone, in seconds?” I wonder. I conclude the purpose is this: to bring people drinks and snacks as they sit on my sofa, and to shout “Oh my god, you’ve not heard _______? You need to hear _______ right now, because you haven’t really lived until you have!” then run to fetch yet another record, probably from 1968 and by someone who was in a much worse, much more well-known band by 1975. But pulling out records and telling you they’re great isn’t a piece of writing; it’s just pulling out records and telling you they’re great. Sometimes there’s not much more than that to say. As an example of this, I was going to use the self-titled, sole LP by the band Kak, from 1969, which during some weeks is just about my favourite record ever, and to illustrate my case I was going to say that the only semblance of a story I have about it about it is that I saw an original of it at a record fair on the outskirts of Nottingham with old brown sellotape on the sleeve and didn’t buy it and regretted it slightly but then did find and buy another original, a few months later, for less money without old brown sellotape on the sleeve. But then I remembered the way some attractive imagery in a line in the song ‘Bryte N Clear Day’ by Kak had inspired a detail in one of my books and I remembered that, after almost buying the copy with the sellotape, I wandered, in curiosity, three small roads away from the record fair to the building where, between 1992 and 1994, I attended a BTEC course themed loosely around the media, but, upon finding the building, whose corridors I still walk regularly in my dreams, I discovered it to be assiduously vandalised, with almost all of its windows smashed, including the one directly in front of the wall with the Nelson Mandela quote ‘EDUCATION IS THE MOST POWERFUL WEAPON WHICH YOU CAN USE TO CHANGE THE WORLD’ stencilled on it, and I realised that since then I have thought about that trashed former annexe of South Notts College every time I have played ‘Kak’ by Kak, which uncoincidentally happens to be a quite “smashed up abandoned building you have often visited in dreams” kind of album. It’s the first LP in the ‘K’ section of my record collection, next-door neighbour to several formidable albums by three different bands from three different continents who were all called Kaleidoscope, and not far from an album by The Kitchen Cinq called ‘Everything But The Kitchen Cinq’, released in 1967, which I also bought on the day I visited my old college, and have only just remembered to play in full for the first time, well over a year later.

By accumulating records, by feeding the urge to suck them directly into your brain, by being led from one record to several more, you are simultaneously cutting yourself off from records, taking yourself further from the kind of attractively intimate relationship a person who owns, say, sixty albums can have with their album collection. After it’s been foraged and brought back to the lair, onto the alphabetised shelf an LP goes, becoming, until its next airing, a grain of sand, a droplet of water. The system can’t work any other way, unless you wish to live in constant chaos, surrounded by piles of love and history, which, in my heart of hearts, is precisely how I do want to live, the snag being that I also wish to be able to perform other actions, such as walking unimpeded to the kettle and, when I want to listen to ‘The Quiet Joys Of Brotherhood’ by Richard & Mimi Farina, heading directly to the ‘F’ section and locating their ‘Memories’ LP in a matter of seconds, as opposed to weeks. ‘Memories’, released in 1968, two years after Richard’s death in a motorbike accident and five years after the elusive novelist Thomas Pynchon served as best man at his and Mimi’s wedding, is my favourite of their albums, but it’s my copy of 1965’s ‘Celebrations For A Grey Day’ which is arguably the more interesting artefact since its cover features a tiny original 1967 sticker - probably placed there by the record’s original owner - of the legendary anti-Vietnam poster ‘War Is Not Healthy For Children And Other Living Things’ designed by Lorraine Schneider. I have checked and, while ‘Celebrations For A Grey Day’ is available on Spotify, the sticker isn’t.

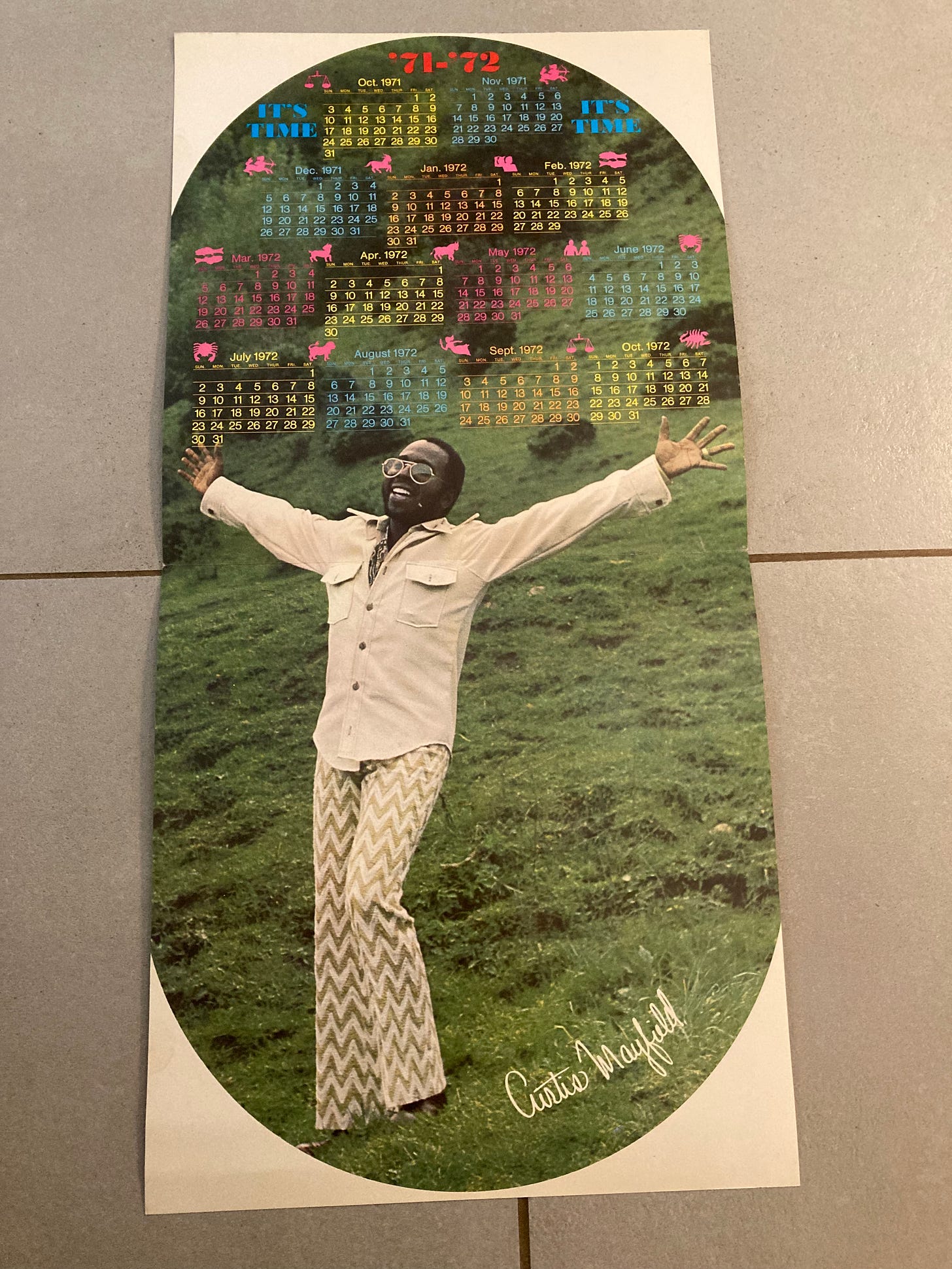

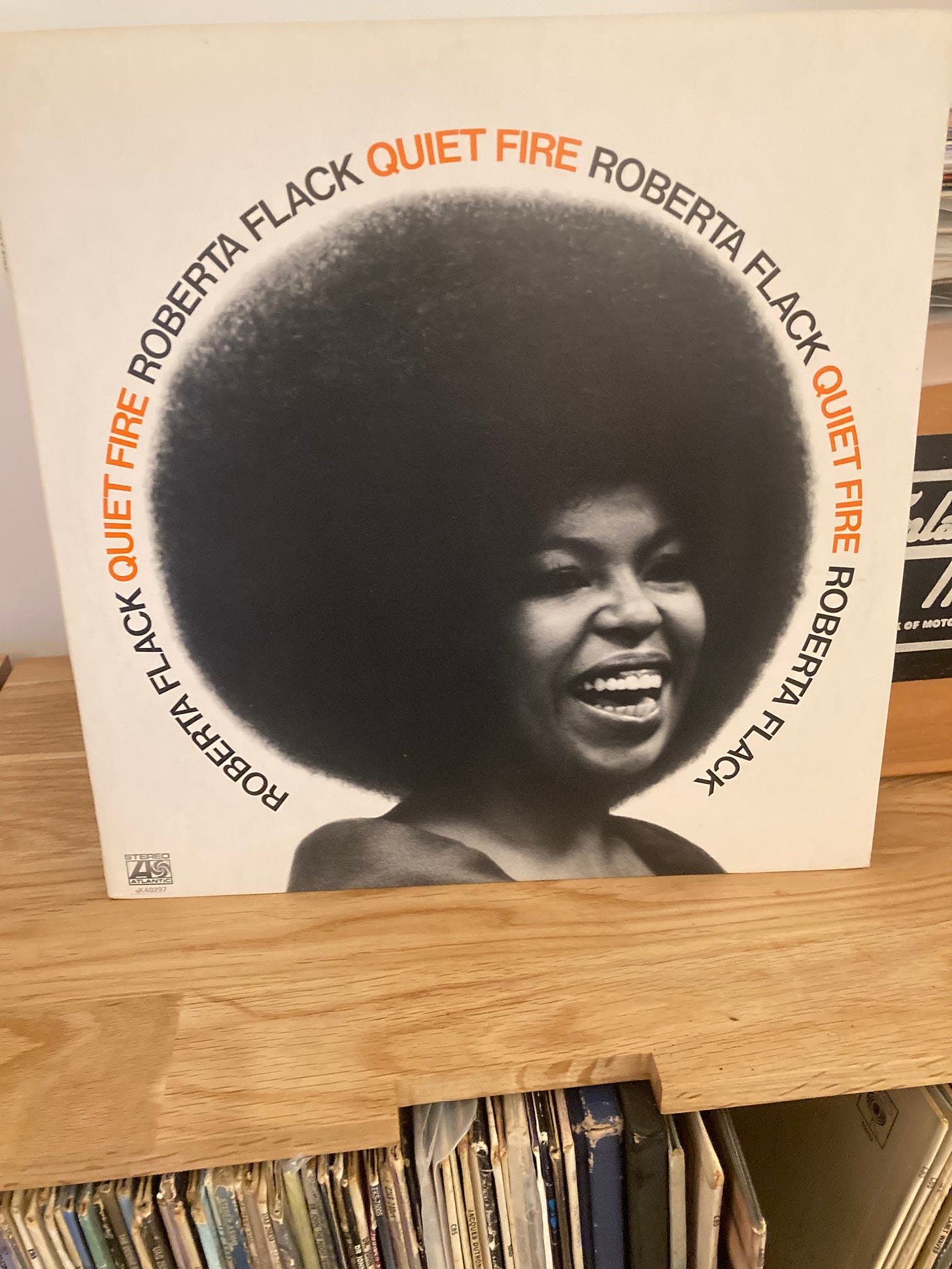

I regularly reorganise my record collection, sometimes out of necessity (house moves) but mostly just to keep my relationship with it honest and solicitous. Off the shelf it all comes and soon the love and stories and lives flood out: the letter to someone called Phil from a bloke who knew Banana from The Youngbloods that I found inside Jeffrey Cain’s ‘For You’, the free 1971-72 calendar inside the original pressing of Curtis Mayfield’s ‘Roots’ that my uncle generously gave me in the late 1990s in exchange for the CD reissue, the poster that came with early copies of Moby Grape’s debut album with drummer Don Stevenson’s middle finger gesture blurred out, the original typed press release in Frost And Fire by The Watersons, none of which are, at the time of writing, available on Spotify. Every record is a train on a branch line to somewhere else. Refiling the ‘F’s, I remind myself how transcendentally out of this world ‘Go Up Moses’ by Roberta Flack from her ‘Quiet Fire’ album is, and notice that Hugh McCracken played on it, which makes me realise it’s been a while since I listened to ‘Agatha’s Raven’ by Mike Corbett and Jay Hirsh, which Hugh is all over, which obviously means I need to dig out McCracken’s own criminally little-known freakbeat 7 inch ‘You Blow My Mind’ from 1965. After this lengthy interlude it’s time to sort the ‘G’s and I immediately spot Sam Gopal’s scuzzily psychedelic ‘Escalator’ LP - not an original, I can’t afford one of those - and think of snakes. It’s 23 and a bit years ago and I am in a pub in Kensington. I have been sent there by a newspaper to interview and drink whisky with Lemmy, who was in Motorhead and before that, slightly less famously, Hawkwind and, before that, much less famously, Sam Gopal. We are having a good chat: about books, and roadying for Hendrix (him, not me; I was minus nine at the time) and the one unforgettable night in 1968 when all of the songs on ‘Escalator’ came to Lemmy, instantly, as if from outer-space. When the record company PR sidles over to tell me my time is up, Lemmy waves him away. “No, I’m enjoying this,” he says. I realise at this point that I have another question I’ve been meaning to ask but haven’t. “Are you scared of anything?” I ask Lemmy. “Nothing,” he replies. He pauses and frowns for a moment, as if an idea has suddenly occurred to him, just like the 11 songs on the Sam Gopal album did. “Oh, maybe snakes,” he says. “It’s because they’ve got no shoulders.”

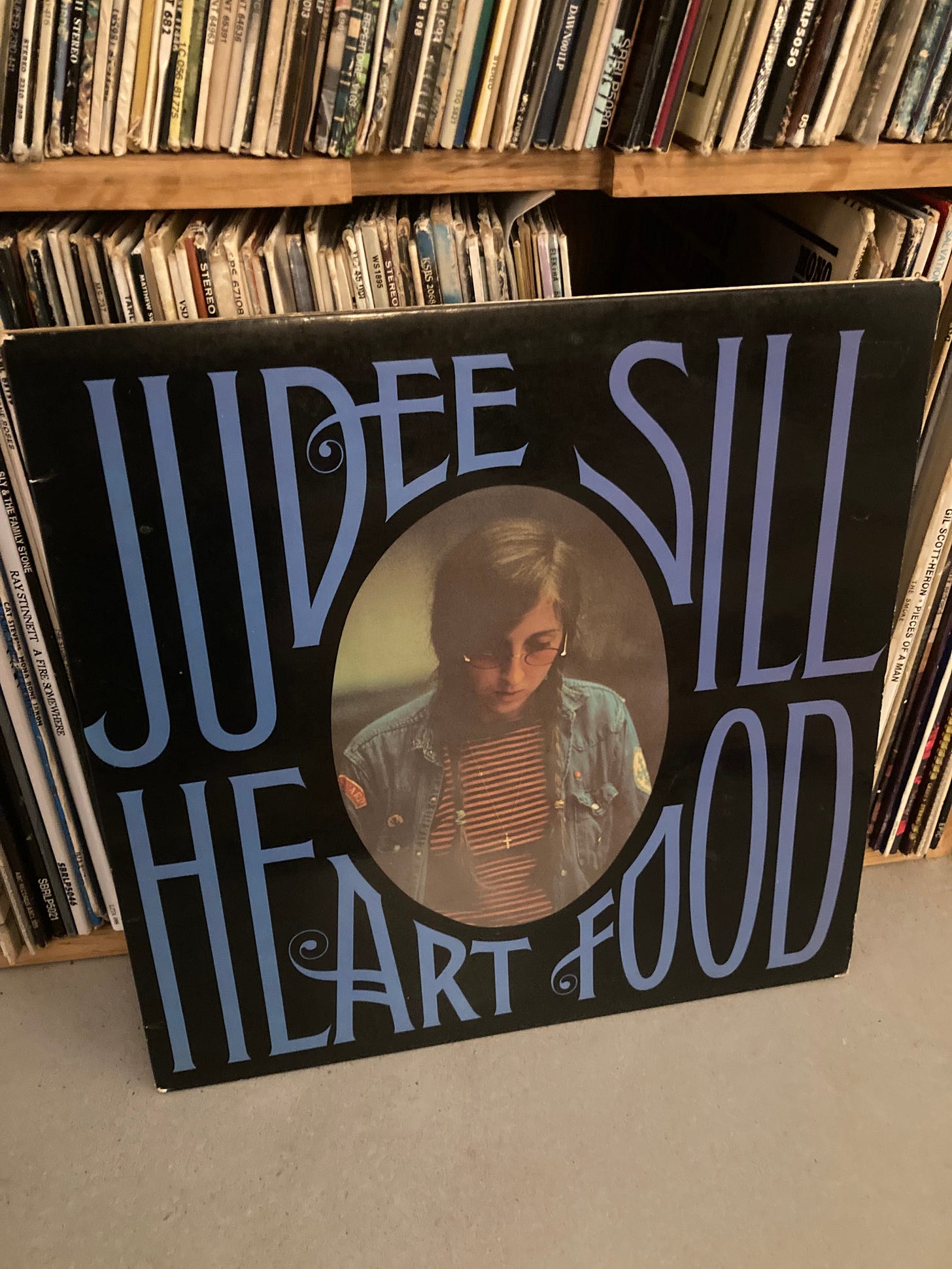

Shuffle across to the right a bit, past the six immaculate Bobbie Gentry LPs I bought in a record shop in Palmer’s Green when I was 25. Here’s ‘Bee Thousand’ by the Dayton Ohio band Guided By Voices. They’re to blame for all of this. 1994: me listening to this very record for the first time, in my bedroom, two rooms away from where it was playing on a cheap turntable donated to my parents by a friend. It was an anomaly: the PR companies always sent the fanzine editors CDs at that point, but they happened to be fresh out on this occasion. (“We have the vinyl though, if that’s any good to you?”) I heard something in there which turned my head: atomic particles, history, something more rich and scholarly than the other lo-fi American music I listened to at the time. It made me want to swim more deeply into the record. A year or so later: me and the band’s singer, a former teacher called Bob Pollard, and the rest of the band’s entourage in the street outside a northern gig venue, Bob telling me about the records he’d bought at Selectadisc in Nottingham that had since been stolen from the tour van. There’s a Swedish girl hanging about wearing a t-shirt with the word ‘PENIS’ on it, which is occupying a lot of people’s attention, but I just want Bob to tell me what was in the bag. “Oh, there was the choicest shit in there, man,” he says. “Cream. The Amboy Dukes.” I already have ‘Disraeli Gears’ by now and love it and the way Bob says “The Amboy Dukes” in his midwest pack-a-day voice makes me want to find out who they are, instantly. The following day, I hit the top floor of the main Selectadisc shop: the bit I always used to overlook because I was always too busy downstairs ogling expensive import Violent Femmes CDs. I don’t find anything by the Amboy Dukes but I do find an intriguing record called ‘Heart Food’ by Judee Sill which I decide is worth a gamble for £1.49. I set out on a mission to find all the constituent parts of Guided By Voices’ sound: the Yardbirds, all the bands on the Nuggets and Pebbles compilations, Peter Gabriel-era Genesis, Cheap Trick, all The Beatles songs that didn’t get played by my family when I was a kid. I’m supposed to be arguing about Blur and Oasis, like other 20 year-olds of the period, but I’m not interested. Why would I be, when I’ve just heard ‘Seven And Seven Is’ by Love for the first time? Then, more excitingly still, I discover the cupboard.

The first look inside the cupboard was when everything began to escalate. It was big and old and located about two hundred yards from my secondary school and overseen by another teacher: my uncle Chris. When he opened it, stories and love and life and experience spilled out into the room, just as they do now when I disorganise my record collection in preparation to organise it again. An album was removed from a brown sleeve and placed on the turntable. It sounded like a record I’d tried to dream into existence as an extension of my recent obsession with the self-titled second album by The Band, touched by similar genius: sort of country, sort of roots, part storytelling, part bruised-but-wholesome post-Woodstock outdoor person vibes. I was told it was by the Grateful Dead and called ‘American Beauty’. I didn’t know quite what I’d expected the Grateful Dead to sound like but it wasn’t this. I saw my uncle differently from then on: yes, he was still the Chris who dressed a bit like a few other teachers I knew and had once been a bus conductor in Great Yarmouth, but he was also now the Chris with an encylopedic knowledge of cutting edge roots, folk, jazz and West Coast rock music made between 1967 and 1971 who’d attended the legendary 1970 Isle of Wight Festival. As well as a whole new, detailed, labyrinthine conception of the late 60s, I can thank Chris and that cupboard for my copies of - amongst many more - ‘Bitches Brew’, ‘Music From Big Pink’, ‘Workingman’s Dead’, ‘Forever Changes’, ‘The Notorious Byrd Brothers’ and John And Beverly Martyn’s ‘Stormbringer’ and ‘Bless The Weather’ and I can’t play any of them without thinking of it, or of all the other albums in it that I might have missed, or dismissed at the time for being “too jazz”. Can you be forgiven for not quite being ready for jazz, at 22? I reckon so. Also, I was already overextending myself: I was writing about new music for a living by that point yet simultaneously hurtling into the past like someone who’d lost all control of his feet in the sheer thrill of running down a hill in high summer. I would need to go back, find the shoe and scarf and wallet I lost along the way, take a calmer, more considered look at the landscape.

I am still going back now, and surely always will be. A record collection is, even as it reveals to you its epic, satisfying archaeology, a reminder of your errors: the time you decided James Brown only had four or five good songs, that Jefferson Airplane only had one album worth owning and Hot Tuna weren’t worth investigating at all, that Philamore Lincoln’s ‘The North Wind Blew South’ was a bit psych lite and to be dismissed so quickly that you didn’t realise one of its best songs was about an area less than a quarter of a mile from the room where you learned to write. There’s always more to rediscover and re-evaluate. I’m quite a long way through the alphabet now. I’m on the big one: “S”. Judee Sill. Sly Stone. The Supremes. The Smoke: the British one and the American one. St John Green. Nancy Sinatra. It will take a while, especially as, like always, I’m going to want to listen to the entire Stone Poneys discography, especially their too-little-heard, slightlydelic third LP, which is pretty much Linda Ronstadt making her own version of Tim Buckley’s ‘Goodbye and Hello’, and of course ’Transformer’ by the mysterious Harvard mathematician David Stoughton which, on some days, is my favourite album released by Elektra (yep, even better than ‘Strange Days’, ‘Forever Changes’ and ‘Da Capo’). And I haven’t even started on the jazz or the Indian or the African or the spoken word yet. I should probably stop, not get any broader in my musical interests, not go down any more rabbit holes. It’s looking like everything is going to fit snugly into the space I’ve allocated for it. But I just got a text from a dealer I know. He says he’s bought a collection: lots of stuff that’s right up my street. This is the problem with getting to know dealers. It gives them more opportunity to quietly watch and learn. They have their own inner algorithm.

BUT LOOK IT’S RESEARCH ISN’T IT. One of the main characters in my next novel - the one I’m writing now, which comes after this one, which I’ve finished - is a record dealer. So it’s crucial that I spend a lot of time in the secondhand record universe. Yes? And, if I buy some more records while I’m there, then so be it: it’s more texture, more colour. I wouldn’t want to forget what buying a record felt like, would I? That would be awful. I mean, strictly in creative terms. I suspect I’d probably be able to stream most of the records this dealer who just texted me wants to show me, but last time I saw him he told me an entertaining story about coming into ownership of Townes Van Zandt’s moccasins. And while Spotify might be able to play you ‘Our Mother The Mountain’ for a small monthly fee, it definitely can’t do that. At least not yet. Neither can it - for all the sophistication of its algorithm - synthesise the excitement there is to be felt in a room full of records. I still feel that excitement, as keenly as ever. Sometimes, to the point I can’t audibly contain it. I remember a few years ago, record shopping with a few friends, including one who’d bought her then partner who said he wasn’t really into vinyl any more because he didn’t see the point of it, when everything was there, accessible without physical clutter, on his phone. I remember him mimicking me, a little cruelly, when I made a sound touched with mild hysteria upon seeing a quite rare album for a competitive price, before thrusting the record at another member of our group who I suspected would love it. To be fair to my impressionist, it was quite a ridiculous, and undoubtedly startling, exclamation: half intake of breath, half girlish squeal, yet somehow giving the appearance of emanating directly from my ears. And here we arrive right back at the problem originally mentioned: that of the outmoded robot attempting to offer a useful and relevant service amongst a coldly sophisticated system of data banks and GDPR oversteps. After all these years, all this amassing of so-called musical “knowledge”, I’ve ultimately got very little to offer outside of an embarrassing shriek of enthusiasm and a strictly subjective assurance of quality.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Villager to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.