It’s been a wet autumn: the kind of wet that, at times, has looked and felt not unlike a trailer for apocalypse. I think of the village where my mum and dad live, in the Nottinghamshire-Lincolnshire border lowlands, as a fundamentally dry place - a sharp contrast to the steep dripping valleys of Devon, where I have resided for most of the past decade - but a few weeks ago, after days of unremitting rain, brown water spilled over the sides of the small river that runs through its centre, into the surrounding meadows and gardens and, within a few hours, the downstairs rooms of people’s homes. By the second day, the flood on the lane at the village’s low point was waist-deep, and my dad waded over there to do what he could to help those trapped who were trying their best to protect their pets and possessions. As he did, he stepped carefully, trepidatious of manhole covers - “THEY COME OFF WITH THE FORCE OF THE WATER AND THEN PEOPLE FALL DOWN THE HOLE: IT’S ONE OF THE MAIN CAUSES OF DEATH IN FLOODS,” he told me on the phone - and, as he glanced through the windows of the houses down near the river, he noticed sofas and chairs bobbing around, buffeted by gentle living room currents. He and my mum were two of the lucky ones: the slight incline leading from the river to their house meant the water didn’t quite reach the building, but it was touch and go for a while. As I received their reports of the relentless rain and the flood’s progress, I worried about their two cats but the first part of the house I thought of was single storey chunk they’d had added to it around a decade ago. I imagined its contents - an unquantifiable number of linocuts, embroideries, paintings, screen prints, collages, charcoal sketches and collagraphs - sloshing about and the images recurred in the nightmare that woke me a few hours later.

My parents bought their house in 1999 and, for the first few years they lived there, there wasn’t a lot of it. Due to the limited space upstairs, when I came to stay I slept on a couple of large sofa cushions in the tiny living room, in which I thought I could sense the ghost of the house’s previous owner, Dorothy House, who had died there on her hundredth birthday. Because Dorothy House had lived in the house her entire life – first with her parents, then with her husband William who ground ball bearings for a living, and then alone – and because it had never been my childhood home, I found it a little difficult to initially perceive it as truly my parents’ house. The fact that Dorothy House had the word “House” in her name somehow underlined the sense that the building was still hers. Upstairs in Dorothy House’s house, there was one small bedroom and one smaller bedroom, which my dad used as an office. Downstairs, behind the stairway and a medium-sized kitchen – the only non-tiny room in the house – there was a narrow utility room, and it was in here, during the middle of the first decade of this century, sandwiched between the washing machine and fridge, that, very quietly, my mum started creating pieces of art. I became aware of this not because my mum had said “Look at this painting I did” but because the art, quite quickly, and in ever increasing quantities, began to appear around the house. “Is this yours?” I would ask, and my mum would confirm that it was.

What had prevented my mum making the art she wanted to during the first five and a half decades of her life? The same stuff that stops endless amounts of people fulfilling the more creative life they desire: a tiring full-time job, the concomitant extra job of being a good parent, house moves and house renovations, a lack of self-belief rooted to an extent in class and background and place. Throughout my childhood, in addition to his work as a supply teacher, my dad sold paintings to galleries, then, in his late 40s, began to write children’s books, but I had no idea about my mum’s artistic desires, as she never mentioned them. When I did become aware of them, it was not because of the volume at which my mum talked about her ambitions, but because of the volume of her output. All of a sudden the house was full of art. Actually, the house had always been full of art – most of it my dad’s – but now few bits of bare wall remained.

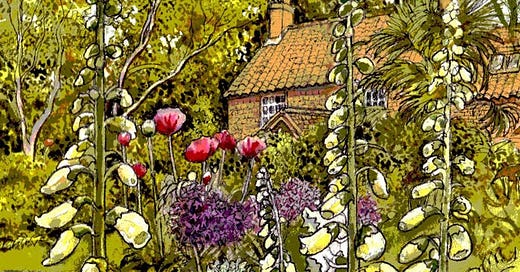

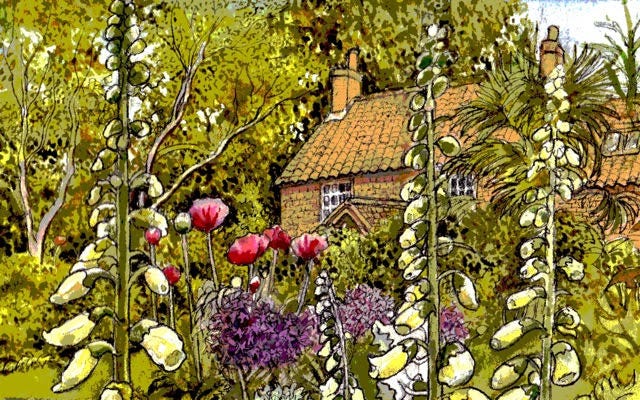

I always liked my dad’s landscape paintings as a child, but it’s only as an adult that I appreciate their fine detail on a higher level: the astonishingly intricate winter trees of his Peak District hillsides, a bucolic yearning for an unspoilt place that’s very him, combined with a slight rawness, an absolute refusal to be at all twee, which is also very him. He’s a little dismissive of these paintings now at times, preferring to concentrate on his blackly comic and more free-flowing new direction: nightmare vistas, grotesque faces, dark mind maps and twisted reimaginings of popular legend (‘The Tickling To Death Of Jesus’, ‘Winnie The Pooh And Tigger Get Assassinated’), plus – on a lighter note – the ‘Slow Down For Ducks’ sign that he was commissioned to paint for the village. But my dad is still arguably the traditionalist in the house. A look around my mum’s work room – her new work room, behind the old work-and-utility room, where a couple of Dorothy’s old sheds used to be – might reveal, to name just a few: screenprints of dried flowers, an embroidery of my cat Roscoe, a still life of flowers and a mid-century jug, charcoal drawings of fish in a frying pan, various abstract landscapes, an athletic man made from a coat hanger, a collagraph of a hare in woodland.

“And since he didn’t know he couldn’t fly, well of course he did/ ‘Cause he’s one of those who knows his life/Is just a leap of faith/Gotta spread your arms and hold your breath and always trust your cape,” Jerry Jeff Walker sings, on his 2001 song The Cape. When my mum remembers the way she started with her art, after decades of working as a primary school teacher in Nottingham, it’s a song – the Guy Clark version, specifically, and mainly that line about flying because you don’t know you can’t – that she often thinks of. As well as being about faith and self-belief and some of the stuff society erroneously tells us will be sapped from our lives as we get older, it is also, I think, a song about magic – an intangible something we need to trust we can tap into, whenever we’re doing anything brave. “I’d been doing art with kids every day of my life, but it occurred to me I’d never painted a picture myself,” she told me recently. “So I sat in the garden and painted the picture.” This would have been in 2005 or 2006. She framed the finished article, an acrylic rendition of some aliums she’d planted nearby, in a wooden frame bought from a flea market, also painted by her.

My mum believes she was steered towards painting actual pictures by intensive home decorating and upcycling furniture: years of rag rolling, vinegar painting and wood-grain stencilling bits and bobs she would magpie from carboot and jumble sales. There are few forms of art she hasn’t experimented with in the last decade. She has also run and attended art classes, including life drawing. On one occasion, the model turned out to be a well-known local postman.. “EVERYONE RECOGNISED HIM BY HIS SACK,” my dad interjected, when my mum told me the story.

So much about a visit to my parents’ house now feels tinged with my mum’s creativity. As I open Christmas presents, I notice each includes a beautiful tag, with a new print by my mum on it. Hares, medieval carol singers. “IF LIBERTY SOLD THESE THEY’D CHARGE A FUCKIN’ BOMB,” my dad comments. For people who profess to be unfussed about Christmas, they’ll both work hard on homemade cards. My mum’s might be a print of a robin, my dad’s a maelstromic cave painting featuring Santa Claus on his sleigh, pulled by three reindeer, charging through a fire and brimstone landscape of hunter-gatherers and wild animals. My mum’s art room is beautifully light and high-ceilinged and significantly more welcoming than my dad’s, but it is hard to argue that there is any injustice in this, since for years my mum didn’t have a proper art room at all, and if my dad did have an art room as nice as my mum’s he would soon undoubtedly make it less nice by depositing mud from the garden, maps, bathwater-soaked paperbacks and half drunk cups of coffee all over it.

My mum stepped up her work-rate considerably around 2013, not long after her studio was built, in the space behind the narrow utility room, where a couple of Dorothy’s sheds had previously stood. I also played a small part in her new zeal for creativity. That year, which was also the year I went from feeling like I wasn’t going to be permitted to write a book ever again to getting on the Sunday Times top ten bestseller list, with a book that some people presumed was about cats but actually wasn’t but also actually was, my mum started to send me illustrations she’d done of my cats. The first of these was a very quickly executed monoprint of two incarnations of my cat The Bear, which came out of a conversation we’d had about his owl-like spirit, and – despite being extremely minimalist – perfectly captured a couple of his most familiar expressions: sweetly hopeful while consumed with obvious worry about the entire universe. Linoprints and embroideries of The Bear – plus my other cats Ralph, Roscoe and Shipley – followed, then the nature and folklore prints she did for my books 21st-Century Yokel, Ring The Hill and Help The Witch.

After seven years of readers of my books purchasing my mum’s art, I have finally just about convinced her that this happens not solely because people like my work and see her as an extension of it. I have no doubt at all that many people who have read my books now get far more excited at the prospect of a new print by my mum than they get by the prospect of a new book by me. “Eek! All those years and I haven’t done enough,” she said, when, for this piece, I asked her to verify the year she retired. How much more, I wondered, does she think she could have done? Her work rate is already astonishing, particularly considering the severe arthritis in her hands, which makes many of the printmaking techniques she uses – including the cutting of lino – more painful and arduous for her. Sometimes she’ll hand me some “spare” pieces of her work she deems “not quite good enough to sell”. I’ll peer forensically at the ink but not see a fraction of anything wrong with any of them. It’s frustrating, dealing with someone who operates on this level of perfectionism, but I can hardly speak, since I suffer from a similar affliction. The part of me that, even though next year he’ll publish his sixth book in seven years, is miffed at himself for not publishing twice as many during the same period: that is one of the parts of me that’s my mum. The part of me who sees a criticism of his work and, even though the criticism comes from someone who hasn’t read his work or has read his work and is the kind of person who would never appreciate it, thinks, “Right. I’ll just have to try harder and write better stuff, then!”: that is also one of the parts of me that’s my mum. When you consider that my dad is a perfectionist too, it’s obvious I never really stood a chance. But, of course, I would not have it any other way for all the world. Being more of a massive bastard to myself – within reason – is why my recent books are better than my earlier books. I also can see a way that the work my mum has done for my books in itself has made me more of a perfectionist. It’s so good, it makes me want to raise the standards of what I do to meet it.

My favourite piece of my mum’s art is probably the painting that you see at the very top of this piece. The choice is swayed by sentimentality: it’s an abstract interpretation of the building I rented from early 2014 to late 2017 on the Dartington Estate in Devon, which I used to think of as The Magic House, place that always felt imbued with a mystical otherness. My mum’s vision of it encapsulates it more than any more traditional one of it could and feels to me like something some visionary artist, living on the estate in the 1930s when it was a virtual commune, might have come up with. Her friend Jane owns the original. Jane lives in Australia now. The last time she and her husband Cliff visited the UK, they got together in person with my mum and dad for the first time in many, many years. My mum said the bag Jane had slung over her shoulder looked familiar. “Yes,” said Jane. “You made it for me in 1969. I still love it.”

My mum was always making something, even when she barely had time to. When I was eight or nine, at my request, she made me a cape. It was light blue with a red “T” that she embroidered on the back using her ancient Singer sewing machine. After I’d flown around the garden for a few hours in it, being a superhero – presumably, going on the logo, a fairly mundane East Midlands one just called “Tom” – I’d often spend the rest of the day indoors, writing or drawing. My mum and dad might have nudged me towards both the latter activities but they didn’t have to nudge very hard; I was always enthusiastic. I remember the feeling of total immersion, losing track of time, feeling that, when I came out of my writing or drawing because it was time for tea or to go out to my nan’s or to go to swim at the leisure centre, I was waking up from a dream. I think my working method resembles this more now - a time when, coincidentally, my love of capes has resurfaced - than it ever has in my adult life. But I’m not the only one, and I don’t think I could even claim that, of my family, I’m even the most immersed. Some people go on fancy holidays in their retirement; my mum and dad – when they’re not gardening – paint, write and draw. “What have you been up to today?” I’ll ask my mum. “Art,” she’ll reply. “What about dad?” I’ll say. “Art,” she’ll reply. I sometimes wish they’d take it a bit easier, go on more breaks. But doing nothing is not in their nature, and I doubt it would make them as happy. There they’ll be, lost in their imaginations, in this house that now seems so much more theirs: my dad in his office, upstairs, and my mum in her lovely, light room, where Dorothy’s sheds used to be. Then, as if by magic, it will be several hours later, and time for tea.

More pieces you might enjoy:

Old Litkinov

I wrote this short story at the end of December. I have already posted it, buried at the end of a collection of mini fiction which was for paid subscribers only but I feel, with hindsight, it might deserve a page of its own. I’ve got some more short fiction coming for paid subscribers in a few days and - who knows - maybe this might tempt two or three p…

The Gun's Always Loaded, The Horse Always Kicks

I was going to make this a paid-only post because in some ways it feels like quite a personal thing to write about, but then I felt like I was being mean to other people who subscribe and can’t afford a paid subscription, so it’s free. But every paid subscription does help me write more stuff like this. And if you take out a full annual one, I’ll send y…

Once Upon A Time On A Lane

A few of you - but probably not loads - will have read this before but, while I put a few finishing touches to a new piece ready for Sunday, I wanted to post it again, in slightly spruced up form, for those who haven’t. It’s one of my favourite things I’ve written on Substack, and ties in as background to a couple of pieces I’m planning to post in the n…

As a contemporary of your parents (and mother of a son called Tom!) I'm utterly charmed by this piece - not just by the two of them and their abundant creativity, but by your tender and thoughtful appreciation of them, while cunningly avoiding schmaltzy tweeness! Bless you!

In the work I do with my clients I always see this shift. Once we have sorted out their SHEET, they want to start digging into their creative side. It's almost as if that's what we are supposed to be doing, and AI should be doing all the shitty tasks, like cleaning the shower (why on earth isn't it self-cleaning?).