Your Billions Will Not Grant You An Exemption From The Indignity Of Death

A compendium of small thoughts about money, the technowanker apocalypse, weather, history, music and semi-colons

If you are a tech bro billionaire, you can delete the receding hairline your ancestry has saddled you with and replace it with a tight-knit block of follicular robo-growth, you can change your face, change public opinion en masse with the power of the misinformation you spread via your digital platform and the more moderate and considered voices you are able to algorithmically drown out, send rockets into space, buy yourself a position at the forefront of political life despite being singularly unqualified for such a position. You can, because of all this, probably convince yourself there is in fact nothing you cannot do. But here you will be incorrect. What you can’t do is ever be a reflective, compassionate human being who can grasp, with any feeling, the harm of your actions. The bubble of unreality you have constructed around yourself - the one which no longer contains anyone who tells you the truth - will be too well-insulated for that to be possible. You would probably believe you are enhancing your legacy with each additional chunk of power you purchase if you hadn’t already dismissed the concept of “legacy” due to your conviction that, for yourself (although not for the minions) you can invent everlasting life. But, despite what you have convinced yourself, one day you will, just like every one else, die. In the final moments, you will be reduced to something frail and helpless. Your billions will not grant you an exemption from that. Maybe right then, in that reduced state, the last thing you will see is the true horror of what you were: the rippling evil of all the choices you could have made with your money and didn’t, and the repercussions for the planet. Then it will be over. Those voices - the ones with no capacity for critical thinking - who said, “I f***ing love that dude, he really tells it like it is - I wanna be rich like him one day!” will gradually fade. All that will remain will be the more rational and sane voice of history above your grave, announcing, “Here lies the most heinous piece of shit imaginable.”

Yesterday I was listening to David Remnick’s interview with Ro Khanna on the New Yorker Radio Hour podcast, originally broadcast earlier this month. I arrived at their conversation as someone unfamiliar with Ro Khanna, who, it turns out, is the US representative for California’s 17th congressional district, and I was immediately struck by his gravelly eloquence and humanism. I assumed it was the kind of gravelly eloquence and humanism that belonged to a guy in his early 70s: one of those calm and rational voices you sometimes get on the fringes of politics who’ve been wisely sidestepping the limelight for decades, and whose calm rationalism seems to flow, at least in part, from that same sidestepping. Therefore I was surprised to discover that he’s a year younger than me: 48. Khanna came across as witty, passionate, astute, warm, empathetic, genuine. In other words, he had most of the qualities you hope for in a leading politician but which, on the few occasions when leading politicians possess some of them, immediately seem to become eroded by the baggage of being a political bigshot. Towards the end of the interview I was simultaneously surprised and optimistic when, having been asked by Remnick if he’d entertain the idea of one day running for President, Khanna answered in the affirmative. It got me thinking about a pattern that occurs so often: the hope that the person you’re seeing running for an important political position might be the one who finally starts to sort it all out, then the various disappointments of their tenure in office, then the bit a few years later when people start saying “Oh, he/she wasn’t soooo bad, really - especially when you look at this giant Satanic tub of dysentery who came next.” This even happens with Prime Ministers and Presidents you never thought were anything but the giant Satanic tub of dysentery in the first place. I read about George W Bush throwing shade to Trump at the 2017 inauguration the other day and found myself thinking “Maybe GWB wasn’t such an atrocious old bucket of homilies” - which is of course nonsense. There’s an early 90s comedy sketch by the magnificent Alexei Sayle I’ve just unsuccessfully attempted to locate on Youtube which describes this phenomenon far more wittily than I have here, and the fact that the sketch is well over 30 years old adds to the argument that the “ooh this person might be the answer - oh no they’re not - oh, actually, I wish we could have them back because it’s better than this current shitshow” phenomenon is a timeless, unalterable rule of politics. Coming to terms with that can feel like part of the shattering of youthful idealism itself. But I don’t think that’s a reason to stop living with hope or stop believing in positive ideas and quietly considered viewpoints that might help us find a way out of the mess we are in, globally.

It’s one the curious contradictions of life that, aside from a few prematurely wise and self-aware exceptions, people don’t generally discover who they are truly are until they’re out of their 20s yet when the phrase “your era” is used, it is generally in reference to the cultural period a person lived through during their third decade on the planet. I have felt infinitely more comfortably, unapologetically me in my 40s than I ever did as a 20something but I am increasingly aware that when people talk about “my era” they are talking about a chunk of history stretching approximately from the time I left school to my 30th birthday. On one level I baulk at such a definition: I spent much of that chunk doing my best, not always successfully, to hide under moss-covered boulders from the pop culture I was being told to like, whether it was Britpop, the even more hollow notions of “indie music” of the early 2000s, or the exploitative meanness of early reality television. But at the same I have found my thoughts turning back to the 90s quite often of late, remembering some extremely good things about that time, and not quite permitting my acute awareness of the own middle-aged sentimentality I’m indulging in to halt the cascade of my nostalgia. Part of that is a yearning for smallness and space, for correspondence that takes place on paper not screens, for people who are no longer alive to be alive again, for something intrinsically anti-bullshit that the 90s always seemed to offer, and another part of it comes from a growing desire to write about that period and some of the positive parts of it we perhaps didn’t place such a high value on at the time. When I receive a mental image of myself and my friends and my family during the 90s, it has an almost pre-Industrial Revolution feel to it. It’s of innocents, blundering around in a time when immense room still remained between the furniture. But no doubt we felt nothing like that at the time. We felt, like all generations always do, like people at the scab end of history. “What could ever possibly be more modern and hectic and cynical than this?” was the constant question in the background of our lives. And I’m sure people now - people who have a more genuine official claim on now to be “our era” than I do - live with the same question as their wallpaper. But has the question become more difficult to answer than it used to be? I feel like it has. I probably would say that, though: I’m no longer a young person. But I do possess a half-decent imagination, and, no matter what I try to come up with, I find it hard to conjure a viable picture of the future point that will prompt us to look back at 2025 and say, “Ooh, weren’t we innocent and slow and primitive and uncynical back then?”

The weather is atrocious here today in the south west of the UK. I’m talking “just saw one of my cats fly past my kitchen window, two feet off the ground” atrocious. I feel reposefully frightened of it, as if my atavistic knowledge of weather’s ability to kill me is at war with the philosophical part of me that remembers all the times I experienced extreme wind and rain and didn’t die. The weather did a minor version of what it’s doing now on Thursday before I walked in Somerset with my friend Jon. We were on the way to our walk’s starting point, listening to the rain machine gun the windscreens of our cars, feeling like we were being physically attacked, but then we pulled up the hoods of our anoraks and got out into the teeth of it and the teeth were nowhere near as big or serrated as we had imagined. I find this is often the case with weather, and much else in life: the worrying thing outside your door is not as worrying when you look it directly in the face as it seemed when you were avoiding it from a position of superficial safety. Having said all that, I will not be venturing out into the weather today. I have some pretty firm rules about the way I live and one of the firmest of all is that I get to break them when I suspect they might inconvenience me.

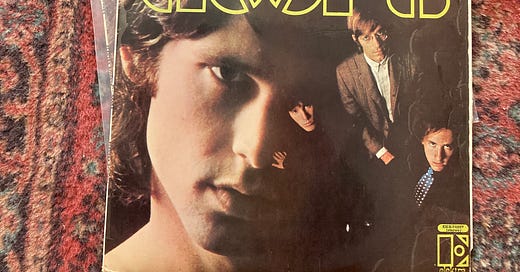

I made the error of going on the internet and expressing my love for The Doors the other day. A few repliers misread this and thought that instead of saying “I love The Doors” what I’d actually said was “WANTED ASAP: some strangers to tell me why I’m officially incorrect to enjoy this music I have, over a long period of time, become 100% sure I enjoy.” This eventually led me to being accused of practicing something “a bit like communism” for expressing the view that such replies were, just maybe, a tiny bit tiresome. I find it fascinating how The Doors, who were once considered a radical and hip band, have through no actions of their own more recently become a stick to rattle against fenceposts for people who want to broadcast the errors they have avoided on their own impeccable personal journey to being above suspicion as a music fan. A proper investigation into the reasons behind that is a whole other piece, and one I feel increasingly compelled to write, especially as someone who once fell out slightly with the music of The Doors, but on a more general level I do wonder what people are trying to achieve by travelling the internet telling strangers that they’re wrong to like the music they like. If we all did that every time we saw an opinion we disagreed with, none of us would ever sleep. By saying “This band/record you have been so foolishly, publicly vulnerable to announce that you love is in fact a load of garbage!” you’re not going to make people suddenly reply, “My god, oh hippest tastemaker. Thank you for making me see the error of my ways. Please guide me deeper on my journey with your profound and correct-thinking wisdom.” It’s just a boring waste of time. If you disagree with something, that’s fine, but it is possible to just stay quiet about it and focus your energy on something more positive. Many of us manage that kind of restraint every day. Nobody is paying you to be a music critic and, even if they are, you shouldn’t be practising your trade in another person’s replies. You’re putting nothing positive out into the world by killing people’s joy. All you are doing is saying, “Hello, I have never met you, but I am superior to and cooler than you because I dislike a piece of art that gives you pleasure.” And nobody properly cool ever does that.

You might find me here, in one of these newsletters, telling you how I write, but you won’t find me telling you how to write. There’s already far more than enough of that going around, after all. You’re you and I’m me and what is a foolproof method for some doesn’t always work for others. John Irving decides upon and writes the end of his novels before he writes their first sentence. I hugely enjoyed several of Irving’s early books but I’d rather wok fry my own aortic valve than take that approach to long form fiction. Irving loves a semi-colon but his former writing mentor Kurt Vonnegut, whose writing I also love, was a strict semi-colon atheist. It seems there’s no in-between in this matter. You’re either a “semi-colons are the only thing that will do, sometimes” person or a “semi-colons have no need to exist and I will gun down every one of them on sight” person; I belong to the first category. However, I’m not going to fight with you if you belong to the second. I believe we can co-exist in peace, separated only by an ocean many thousands of miles wide

Also, I probably don’t need to give you any more of this solvitur ambulando hype. The phrase is Latin for “it is solved by walking” and, since I first stuck it on social media about six years ago, captioning a pretty photo I took near Lulworth Cove, it’s been repeatedly regurgitated and added to all sorts of memes, and, what with the general nature writing boom that’s been going on for long over a decade, the secret is now well and truly out: a lot more people are now aware that walking can be of serious benefit to the writing process. Which, to be fair, a lot of people were already aware of anyway. I’ve written about it too much here already, I suspect. And before me there was Charles Dickens, who, it is often said, would not even skip his daily perambulation during the most destabilising throes of illness. Just because it was me who originally pointed out to Charles that a long daily walk might help him map out the complex plots to his overlong novels and think up even more stupid names for his characters and he never gave me credit for that and I never once called him out on it and his books have sold literally millions more copies than mine, I don’t think that’s any reason for me to stoop to petty jealousy. We are all batting for the same team, and the name of that team is “writing books”. Take, for another example, the other day when I walked with Jon, who having published an invaluable guide to the lost and weird corners of Dorset in 2023, is currently researching a more comprehensive and exciting-sounding book about hilly - mostly south western - landscapes and their legends. The two of us covered more than eight miles in total and talked about all sorts of subjects from King Alfred The Great to the mournful crepuscular cry of eels: an effortless, unguarded exchange of ideas which I am sure was of equal creative benefit to us both. Towards the end, Jon told me a funny story about a swan and another funny story about a badger. “You do know I’m probably going to use those in a book?” I told him. “You can have them,” he replied. Oh yes, I thought, we are all friends here, as I handed over the five figure fee he had specified.

My most recent books are 21st-Century Yokel, Help The Witch, Ring The Hill, Notebook, Villager, 1983 and Everything Will Swallow You. All of them can be ordered from Blackwells UK, who do free international delivery to most worldwide destinations.

I envy your ability to say exactly what you mean without pulling any punches and yet never come off as an asshole. That’s some kind of magic. Also, I found everything you wrote here deeply cathartic and hopeful. Vonnegut would be proud.

Giant Satanic tub of dysentery is a particularly brilliant descriptor and will be popping up in my head quite frequently in the coming years. Thank you for this.

This was an excellent piece and a great Sunday morning read!