I'm Sorry, I Cannot Afford To Purchase Your House, But I Might Well Write Weird Stories Inspired By It

What a week. Today I found out, via this article in the Bookseller magazine and messages from other authors who wrote books for my ex-publisher, Unbound, that, despite their promises otherwise, a trickle of the huge sum of money they have failed to pay me and others for sales of our books will not, after all, be coming through in the near future (and, by the sounds of things, not ever). I probably should have expected this, after all Unbound’s other hollow promises in the past, but I’m still stunned. If this publisher, in its new incarnation of Boundless, paid me all of what they owed me, it would amount to more than £20,000. I’ve long since given up hope of seeing that but I think some optimistic part of me still believed they might honour their promise to pay me a chunk of my earnings. Now, once again, I feel like a fool.

This revelation arrived less than 24 hours after some other less than brilliant news: my partner and I discovered, out of the blue, from our landlady that, in marginally over two months, we have to leave the house where we currently live. As many of you who have subscribed to this page for a while will know, I have written often about the - partly accidental - semi-nomadic life I’ve lived, and to be completely honest, the two of us were already planning our next adventure, but this, unlike the latest Unbound one, was a shock we were not at all prepared for. We are trying our best to embrace it, hasten our plans and my feeling is that, ultimately, it will lead to plenty of new experiences, not to mention some new places to write about here. I also, of course, have a new publisher, and a new novel finally coming out in autumn, so there’s plenty to be positive about, despite the undercurrent of terror that has characterised the last couple of days.

This is all a long-winded way of saying I thought it might be an opportune moment to repost the piece below, which a lot of you will not have read. I wrote it only nine months ago but, after a reread, it illustrates to me just how much has changed in that time, and just what an ugly stick the whole Unbound fiasco has twisted into the spokes of my creative wheel. I still think it’s one of my better Substack pieces, though, and, despite all the stress, I have still managed to be very productive since September, even if the house-themed novel mentioned below remains barely beyond the idea stage.

P.S. I’m now very close to the bottom of the huge pile of books I purchased from my ex-publisher and completely out of Villager, Help The Witch, 21st-Century Yokel and Notebook paperbacks. While the last few piles are here, though, I will be sending out signed hardbacks of 1983 and Notebook, and a signed paperback of Ring The Hill to everyone - wherever you happen to be be in the world - who takes out a full annual subscription to this page. I also have just received 25 more prints and postcards - see photo at the bottom of this newsletter for small sample - from my mum, Jo, which I will also send out to the next few people who do subscribe annually. (I don’t think she sent these specifically to try to assist me in a small way with my upcoming moving costs but the timing was eerily spot-on!)

EDIT: A few of you asked, in the aftermath of yesterday’s developments in the ongoing Unbound fiasco, if there is any way to support my writing for those who can’t afford a subscription, and I’ve now added this donation link on my website.

If you ask me there’s far too much news out there and we would be all better off if it stopped for a while but here’s another minuscule bit: my next novel - number four - is going to be about houses. Houses, what people do to them, and what houses do to people. It’s been coming for a good while and I would probably find it easier to shove a bung in an Alpine waterfall than put a halt to it. I have been obsessed with houses for years, lived in the absurd total of 25 in not even twice as many years here on earth. The obsession has grown out of my varicoloured fortune as a semi-nomad, and what I have inevitably learned through trial and error, via all that relocation, about the difference between what you think makes a house a nice place to live and what actually does. Plus I am in the market for an excuse to learn more about architecture and bricks and stone and tiles, especially as pertaining to the homes of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. As some of you will no doubt be aware, I was in fact alive in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, going noiselessly about my business as one of the more publicity-shy herb women of Great Britain’s bedevilled moss forests, but such a lot of water has flowed under the bridge since then I want to refresh my memory regarding the building methods of the era. Also I had a fucking dynamite idea for a house-themed novel’s title and structure when I was out walking on the moor on Sunday, and now I can barely think about anything else. All this is extra useful because it means that on those occasions when I see a house for sale I’m curious about but can’t afford and try to structure a walk around it - as I did on Sunday - I can tell myself I’m doing “research”, rather than, for instance, just snooping around or living in a fantasy whose only ultimate goal is to lacerate myself for falling off the housing ladder eleven years ago.

In truth, I already benefit from these house-orientated walks, as they often take me to places I would probably not otherwise visit, oddball hillocks and runt valleys foresworn by walking guidebooks and not frequently discussed by other walkers I meet. Sunday’s was a typically varied case in point: I sized up a lonely stone age dolmen in a field, walked into a campsite by mistake and stole from its water fountain, ducked into a Morrison’s Petrol Station and bought a pack of jalapeno and cheddar crisps (note to self: accept that your brief tempestuous love affair with these is long over and gather the strength to move on) then found myself in a dark cartoon farmyard and lost the footpath entirely. Presumably nobody felt there was any need to advertise it, due to the fact only seven other people had used it since 1986. Everywhere I looked, animals watched me with the same doleful “Could it really be that our saviour and guru has finally arrived?” expression. Two cat heads popped up like fur periscopes from deep within a pile of straw on the top floor of a barn. Border Collie eyes trailed me from a dark brickhole in a shed. Seven sheep ran over and tried to help but offered none of the navigational expertise I’d been hoping for. I turned a corner and was almost toppled by the sight of one of their colleagues upside down in the backhoe of a tractor, assailed by flies. When I finally found the path and took it towards the bungalow I’d themed the walk around, it soon revanished. I hopped the fourth fence of the day, checked out the unaffordable bungalow, thought about the life of the veteran horticulturalist who’d owned it, listened to the unceasing roar of the four lanes of the nearby A30 from the perimeter of the garden, imagined the chaos of the extension the building’s underutilised rear begged for. I have no plans to move house. Sometimes I think I go and look at these places just to remind myself how much I like the house I rent right now. It’s a circuitous way of making myself shut up. But it’s about more than that, too.

Big busy roads divide the landscape into tiny countries that never asked to be there. The M5 Motorway - the major route connecting the South West of the UK to the Midlands - makes you conceptualise Somerset in a way that would never have occurred to somebody in 1959 pootling down from Lichfield to a crumbling Torquay guesthouse in a Morris Oxford. The rugged part of the county to the west of the motorway, with its line of injured towns, tracking the coast. The softer part to the east, where the pretty honey-coloured buildings begin, all the gardens contain affable printmakers and the cafes charge you an extra four quid for pan frying your meals and banging on about Maris Piper potatoes. It’s not that simple, of course, but a motorway is a dick politician: a bully, impossible to engage in reasonable debate, who tries to oversimplify everything. You drive along the A30 and the dual carriageway has this way of conning you into falling for the hype that Dartmoor had it personally installed, having decided it would mark the moor’s official northern boundary. In truth, nobody can quite pinpoint where Dartmoor ends, least of all Dartmoor itself. That border is just some tarmac laid in 2006 to enable Londoners to get to their second homes on Cornish estuaries more quickly. But it makes a difference. Hidden from sight by the foliage, its constant, chronic rumble is the land’s invisible pain. It is fibromyalgia for the surrounding copses, streams and meadows. These concrete arteries have the most enormous effect on the character of what surrounds them. Having been forced to accept them as part of life for so long, our eye is drawn to only some of it, but it’s all there. I saw more a few days earlier when I strolled the flanks of the M5, near Wellington, trying to imagine the place pre-concrete rumble, pre-1967. This is an area not without its share of enchanted woodland paths and ghostly dingles, but there’s a particular industrial look about the farms, something unimaginative and lawn-fixated about a lot of the big houses outside of town, as if the very presence of the motorway itself has become a magnet for people with a passion for the unsubtle.

I remember driving south along that part of the motorway in early 2020, past the ‘Welcome To Devon’ sign. I saw the sign and tasted salt as a tear fell to my lip. For the second time in as many years I’d moved away from the South West then, missing it painfully, scuttled contritely back. The Wellington Monument hadn’t reopened to the public at that point. The National Trust were reinforcing it to withstand the remaining few years prior to humanity’s self-willed extinction. I could see it up there in the mist above the motorway, the world’s tallest three-sided obelisk. In its scaffold-covered state, it looked like England’s biggest rawl plug. I still had a packet of standard-size ones in the car, left over from the last move. I’d soon be putting them to use again. Something else I strongly remember from that move: the air. The way it hit me when I got out of the car at the end of the 350 mile journey. How it seemed so full of renewal, so full of the water rushing down the hill from Dartmoor, so full of big steady guarantees of an untrapped life. Breathing it in was like taking a hit off Western England’s bong. “That’s it,” I thought. “Never leaving here again. No chance.” I still feel the same way, but I won’t pretend I haven’t had my moments. Escape is in my blood. I like to at least be able to think about it, no matter how settled I am. It’s also become part of my work, part of that list of stubborn, antithetical actions whose benefits I have reaped. But this is where I live. I am now well-versed in what happens when I leave. Quite simply, I miss it too much: Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Cornwall. The whole eccentric family.

Are we allowed to be contradictions? Does the internet and its Personality Police permit that at the moment? Am I allowed to be a man who loves taking off and exploring new places, allowed to be an outdoor type with muddy boots and river-drenched hair, but also a man who loves his home comforts, who is an incurable fussbudget when it comes to the arrangement of the plants and furniture and books and paintings in his house? Can I be an anti-materialist, with caveats, including the caveat that I can’t help appreciating a lamp base thoughtfully carved from wood in 1961? Because it’s who I am, and there’s no avoiding it. I recently told someone who knows me moderately well, but has never visited my house, that in another life I would have loved to have been an interior designer. The look on his face was the kind you might wear if a badger had told you it had learned needlepoint. But it’s there in me, always - no less in me than the bit that makes me climb trees and leap from stone to stone over rushing rivers. Each of these houses I’ve rented for such a short time, I’ve done everything I could, as quickly as I could, to make their rooms as comforting and warm and easy on the eye as possible. Look at the living room of the house I rented in Somerset, beginning August 2018: a house I knew I was only going to be permitted to live in for a short time. I took this photo less than 24 hours after I had moved in.

I have done this literally every time. Not just shifted my record and book collections and my furniture and that massive wankface of a Dracaena over there in the corner, often many hundreds of miles, but instantly, upon landing, made them look like they’re part of a long term home, a home to make a future in. The person doing this is the person who misses the long term home he did have, back at the beginning of the last decade, the person who fantasises about fully shaping his own space, finally putting up the nice wallpaper he bought from a junk shop a few years ago, planting a tree in a garden and watching it climb towards the sky over the course of a number of chequered years as his hair turns white. The person who no longer wants to live with renting’s inherent precariousness nor, at almost 50, continue to be infantilised by the unavoidable base dynamic of a landlord-tenant relationship - or, even worse, a landlord-estate agent-tenant relationship. But then there’s the other person he shares a brain and body with. The one terrified of mortgages and the tedious and unreasonable questions they always seem to be asking of his working life (“… you do realise you’d be far more eligible for this house if you wrote something more boring and shit?”). The one who gets a buzz from rocking up in a place, getting to know it really well for a few months, then fucking the fuck off. The second person has been created, to some extent, by the barriers preventing the first from getting what he wanted. A decision to roll with a negative situation has, over the last 11 years, created several positive ones. Yeah, it scares me to think how much the house I sold in 2013, that I couldn’t afford to stay in, might be worth now. But it scares me more to think what I’d have missed out on, especially creatively speaking, if I had found a way to stay in it.

What right do I have to complain? I’m not a member of the generation who got properly screwed, house-wise. I’m a member of the final lucky generation, but one of those who didn’t hold onto the back of bus firmly enough when it hit a bump and has never caught up. The bus is so far in the distance now I can barely see it. I was wrong: I thought it was just some 1990s National Express Coach with a top speed of 65mph, with some old guy called Ralph at the wheel. But it turns out it’s being driven by Sandra Bullock, with Keanu Reeves to her immediate right, looking concerned. How did it rush so much further off, again? I had just about reluctantly accepted that the £249,000 bungalow I couldn’t get a mortgage on in 2013 had, albeit in modernised state, become worth over £500,000, but… £750,000? How is that a part of any liveable reality? I scorn the importance placed on all this, as if it’s the meaning of life itself. I abhor the current trend of saying “property” when you mean “home”. No matter how much an estate agent says “the property” to me, I will not parrot it back to them. I will say “the house”, or “the bungalow”, or “ the home”, or maybe even “the building”, but not “the property”. Go swivel. The only reason I’m even typing the word here is to demonstrate how much I dislike it and all it implies about where we are, as a society. Yet I still yearn for a house that my partner and I can properly call our own. A house that’s fully a reflection of us, where nobody can come along and say, “I’m sorry - you have to move now because I’m selling this/putting up the rent/moving back in.”

I know the houses I sometimes fantasise about living in - even the fancy ones - do not hold The Secret. But I still sometimes yearn to own a house.

I know home ownership brings its own set of problems and extra expenses. But I still sometimes yearn to own a house.

I know, from a few curiously passive-aggressive Judgey McJudgerson comments I’ve received from home owners about my recent peripatetic life, that being stuck in one house for a long time can ferment bitterness and frustration. But I still sometimes yearn to own a house.

That move in early 2020, back to Devon from Norfolk, was an anomaly for me. Autumn tends to be my relocation season. It’s happened so many times now, it’s become part of my biological clock. We just signed up for another 12 months renting our bungalow, but my body doesn’t appear to know that; it’s steeling itself for disarray, for lists and cardboard and backache and cleaning and the nearest British Heart Foundation charity shop I can easily park outside, for the juggling of tasks, for the perilous tightrope of it all. I guess it’s also why I find my feet inadvertently diverting on a walk after I have thought “If I took this footpath here, to the left, I wouldn’t be too far from that house I saw on RightMove last week - the one with the attractive, freshly laid oak floors, open-back stairs and the mysterious giant boulder in the garden” then, having seen the place, asking, “What if somebody turned one of my books into a film next year? What if my next novel sells well in America? Could it actually be possible? Could I plant a Trachycarpus in a garden and properly call that Trachycarpus my own?”

Then I tell myself, once again, to shut up.

You see, I have this secret suspicion. The secret suspicion is this:

Making a series of reckless, tiring and financially unwise decisions about where I live, and jeopardising my future security as a result, has made me much better at what I do.

I don’t believe that will always be the case. I reckon if a wealthy Connecticut relative I didn’t know existed left me Philip Johnson’s legendary Glass House in her will - okay, yes, I know it’s a museum now, but let’s say it turned out Phil had quickly made a duplicate on some quiet weekends in 1949 without telling anybody - I could write a damn good book in it. But I believe it has been the case, in the precisely eleven years since I sat in a building I legally owned, sifting through a decade’s worth of life, poised to exchange contracts with an eager couple from Letchworth Garden City, and asked myself, “Ok, what’s next?”

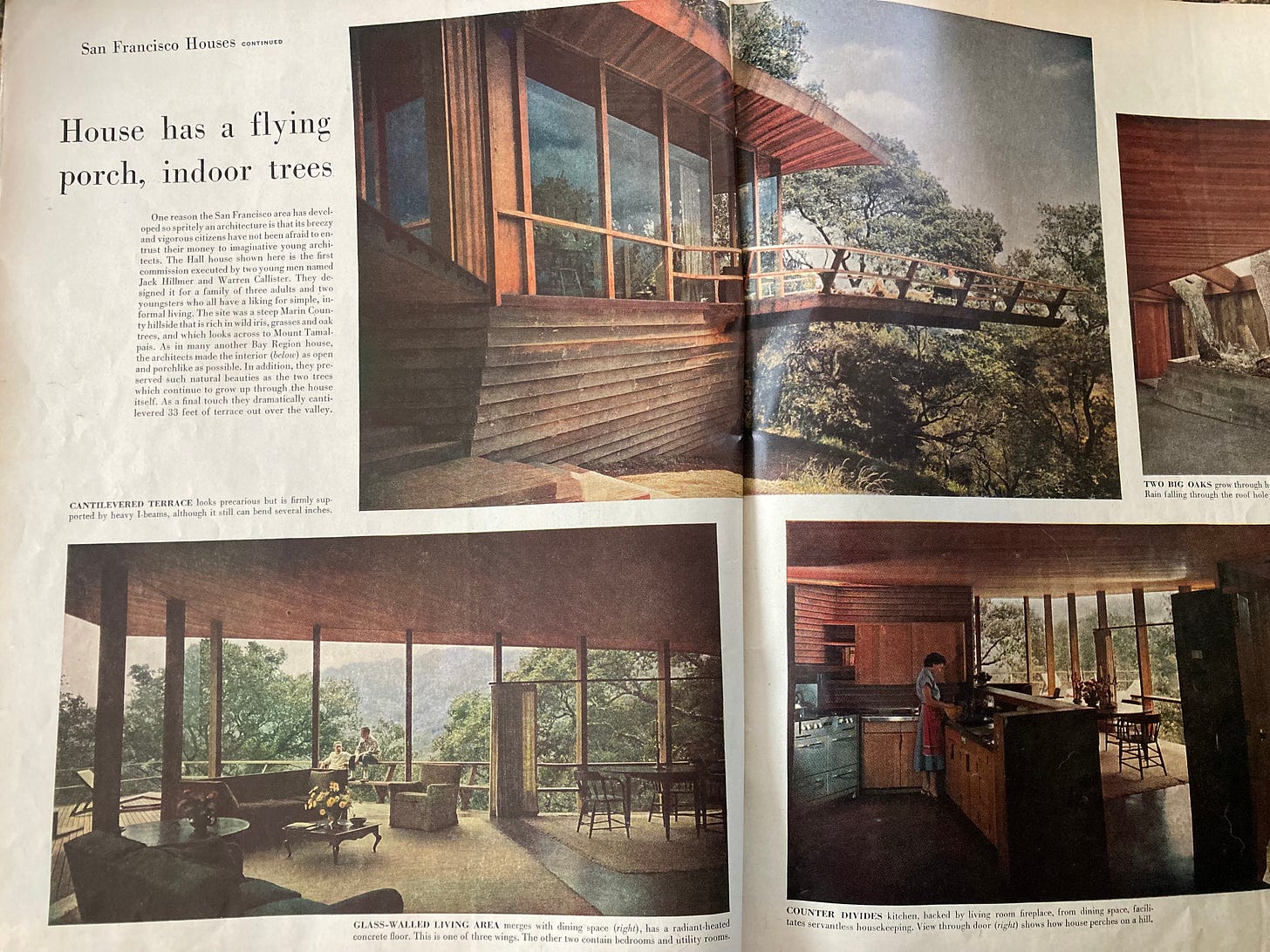

Unfortunately, because I’d earned roughly £9.71 in the previous tax year, what’s next wasn't my own cantilevered canyon terrace and indoor trees plus the rest of this house in Marin County designed by Jack Hillmer and Warren Callister, which I recently discovered via a late 1940s issue of Life Magazine, and which has been making me marginally unwell with longing.

What a gargantuan, unrelenting pisser it is, living in the wrong era, not having a job in computer coding, and liking big windows and expensive bits of wood.

There is no getting away from it: I am terminally obsessed with houses. Imaginative ones made between 1933 and 1970, particularly. But all kinds, really, from all eras. I walk into them and mentally repaint them, strip floors, restore neglected original features, knock down walls. I walk past them and I can’t help telling myself stories about who lives in them. If nobody lives in them, and bits of their walls are missing, I tell myself stories about their ghosts. I love what houses promise, even if the promise is a lie.

I want to write a book about those promises. Hundreds of years of them.

Close to two decades ago, I wrote a weekly column for a national newspaper where I found posh houses that were for sale then went to visit them and reviewed their plus and minus points. I rarely felt a desire to live in any of the houses my editor sent me to, especially the crazily expensive ones. I’ve learned much more about what I like since then, and how a house can dazzle and bullshit you, but the general outlook of my fantasies is not dissimilar: the houses I seek out are never the obscenely huge, luxurious ones (think of the cleaning, for one thing). Yes, the houses I fall in love with are always a little out of the ordinary. They’re rarely covered in greige fixtures and paint, never look like they were designed by an algorithm, are often in beautiful locations, and they’re not what you’d call cramped, but if they’re fancy, they’re fancy in a more modest way. As I look at them, online or in the brick, I momentarily feel duplicitous and untrustworthy. Why? I’m not cheating on our house and I doubt it would mind if I was. I look, and I let the feelings wash over me, don’t hide from them because hiding from them never works. I let those feelings travel through me, on their sweet way, and I learn a little more - about houses, and about where I have got to with all this. I go home, look up an architect, a type of stone or wood, or some unfamiliar phraseology. I think of histories trapped forever inside old walls. As part of the process, I sometimes dream of lives unlived - and probably unliveable unless this Substack newsletter becomes dramatically more popular than it is or Spielberg wants to surprise himself by making a buddy movie about the adventures of a West Country record dealer and the record dealer’s semi-aquatic folkloric housemate - but dreaming isn’t a disorder. If you stop dreaming you end up writing in monochrome, monotoneprobably. It hits me, suddenly, powerfully, that what I’m in fact doing - what I’ve been doing for a long time - is gathering information. It really is research: not by the definition of what you grow up believing research is, but by the greater, richer definition you have learned through the process of writing books, the one whose boundaries you, and you alone, can shape and set. The only person in charge here is me.

Dear Tom, you nearly gave me a heart attack this morning. We are 25 days from the closing on selling our house which has been a long and fraught process but will ultimately be a good change for us. But when my iPhone announced your article, it just showed me “The Villager” and “I’m sorry, I cannot afford to purchase your house.” Guess which part I read first? 😆

I follow your chain of thoughts quite well. I owned a house once for eight years. It was an adventure, being on the edge of a city with the woods nearby and on a dead end road.

Before too long rabbits, squirrels, various types of birds, shrews and even the occasional wayward deer would pass through (a few literally). My first months coincided with the late spring and early summer of the year and the empty lot behind me (which I owned) was a great spot to grow a garden.

But then winter intruded its grizzled muzzle and I soon discovered every drawback imaginable. Since there was no basement or cellar the foundation sat perilously close to the ground.

Mice and shrews soon found the proximity to the kitchen with all of its produce irresistible and I found myself stooping to Machiavellian schemes to trap them. The incessantly freezing temperatures not only kept the house frigid but inevitably froze the plumbing by February, necessitating a trip down to the crawl space with a heater which, over the course of a day and two nights, would finally get the water running again.

Then there was the matter of the roof over the laundry room. The pitch was too low and, as a consequence, ice dams would build up and water would drip down the walls.

I remodeled the room (and roof as much as I could afford to) but the leaking merely migrated, a bird flowing north.

The neighbors across the street would walk through the front yard to the garden, helping themselves to whatever was ripe.

“The people who lived here before always let us do that” was their only response before I laid down the law.

As a last resort I thought that if I could hire a business to lift the house I could at least get a cement foundation laid in. This was, as it turned out, useless as the house, originally a summer home, was built almost room by room, each section having its own foundation - seven in total.

I sold it at a loss to a guy who one day decided to case the house and peered into my bathroom window just as I was taking a shower.

Since then I’ve lived in so many rented houses and apartments that I’ve lost count.