“WATCH OUT FOR GANGS IN NEWARK TOWN CENTRE,” said my dad. “IT’S A FRIDAY NIGHT SO THE PLACE WILL BE TEEMING WITH THUGS, YOBS, NUTTERS, TWATS AND FUCKPIGS.” We were in his and my mum’s garden, where, moments earlier, he had been feeding a vast marauding army of ducks. Back in April only about eight were turning up regularly, but since then word has got around in the Nottinghamshire mallard community, and today we had counted an all-time high of 27, each of them taking advantage of the £60 of bird food my dad, who prefers a maximalist approach to life, purchases every Saturday.

“STAY STILL AND BE COMPLETELY QUIET OR YOU’LL SCARE THEM,” he told me.

“Are you sure?” I said. “They look like they don’t give a shit.”

He squinted at me sardonically, appraising my outfit. “YOU KNOW WHAT? YOU LOOK REALLY SMART AND HANDSOME. IT’S A SHAME YOU’RE SUCH A MASSIVE WASTE OF SPACE UNDERNEATH IT ALL.”

In a couple of hours’ time, I was due at Newark Town Hall, about a quarter of an hour’s drive from my mum and dad’s house, for the first event of a small tour I’m doing to promote my new novel. Thinking forward to the evening underlined the way the pandemic has scrambled my sense of time. In the half-examined chronology of my life, as I generally perceive it, my previous Newark talk took place maybe two years ago. Running in opposition is the cold hard fact that more than half a decade has elapsed since it happened. I have greyer, much shorter hair than I did then and dress more quietly and soberly, which in my dad’s eyes means “better” and “less likely to result in getting pummelled with house bricks by strangers and left for dead in a bus shelter”. I have ambivalent, undramatic feelings about the changes to my wardrobe. I was comfortable walking around in bellbottoms with wild hair half-contained by floral headbands in 2018. I’m now equally comfortable walking around in less flamboyant trousers with a haircut that suits my less exuberant, almost fifty year-old hair. I sometimes miss the way that my sillier outfits would elicit an instant, amused familiarity from strangers. But I also like the way my more recent look allows me to blend into my surroundings in certain ways that I previously couldn’t.

Every time I do a talk, I am struck afresh by much I enjoy the process. Public speaking long ago ceased to hold any terror for me. I find it quite relaxing and could probably rabbit on all night in the doubtful event that somebody wanted me to. There’s also a loveliness about meeting your readers in person that replenishes your creative soul in a particular way that no digital feedback, however passionate, ever quite could. But I am not a person who relishes the limelight. I am a person who relishes being at home, or out in some woodland, alone, with a pen and notebook in his hand.

“HOW MANY PEOPLE WILL BE GOING TONIGHT?” asked my dad.

“I don’t know. I doubt it will be a lot. I’ve not told many people about it. Matt and Alison and Karina and her daughter Daisy and Steve and his girlfriend Sahar are coming. So I can count on six, for sure.”

“I WISH I WAS DOING A TALK.”

“Why don’t you come?”

“YOUR MUM SAYS WE CAN’T BECAUSE WE’LL EMBARRASS YOU AND MAKE YOU NERVOUS.”

“You’re honestly both welcome to be there. I’d be happy if you were.”

“WHICH PUB ARE YOU GOING TO WITH YOUR FRIENDS AFTERWARDS?”

“The Prince Rupert.”

“HMMM. WELL, WATCH OUT FOR FUCKWITS AND LOONIES WHEN YOU’RE IN THERE. THERE WILL BE LOADS OF THEM, NO DOUBT. ALL LAGGED UP TO THE GILLS AND READY FOR A FIGHT. AND DON’T WEAR THAT JACKET YOU WERE WEARING EARLIER.”

“WATCH OUT FOR FUCKWITS AND LOONIES” took firm root as my dad’s catchphrase around fifteen years ago. He will use it - or his abbreviated version, “WOFFAL” - about half a dozen times per day on average when I visit him. On the whole I’ve found that it’s sound advice, if a little overdone. I don’t know that he’s found my grandma Joyce’s catchphrase quite so useful. “The gun’s always loaded, the horse always kicks,” Joyce would say to my dad when he was a small child. At the time, they lived on a council estate on the western fringe of Nottingham. It was the 1950s and horses, though no longer the primary cause of traffic jams, could still sometimes be seen in the area. Upon spotting one, dad made certain to steer well clear of its hooves. Guns were generally only seen in comic books and films, but he remained vigilant, often taking his toy Davy Crockett rifle out with him on his excursions into the nearby woods. Back at home, Joyce fed my dad charcoal tablets for what she called his “bilious attacks” - which he had not realised he suffered from, until she told him - and instructed him not to stick his fingers into plug sockets. When he was a little older and she found him playing with a friend close to the railway line, she called the police, but the police chose not to arrest my dad who, to this day, with his 75th birthday not much more than a month away, remains free of a criminal record. When there was a fight between two of my dad’s peers on the street outside the house, she broke it up by asking them if they were “making love”.

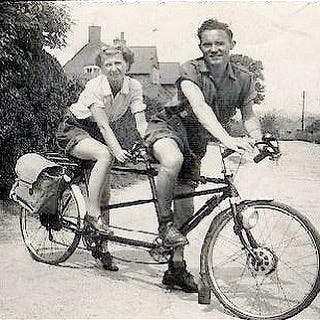

I was never close to Joyce. She scared me a bit, and, when we saw her, I could sense the anxiety she caused in my dad, too. I don’t remember her saying “The gun’s always loaded, the horse always kicks” to me but I have no trouble hearing her doing so in my head, in her voice: a flinty voice, very Nottingham, but also, somehow, a bit “1950s newsreel”. A voice now obsolete. Definitely not my dad’s voice, which is my granddad Ted’s voice - or an equally loud, slightly less carefree version of it. Unlike the rest of us, Ted wasn’t a worrier, which was part of what made his relationship with Joyce successful. Below is a photo of Joyce and Ted in the late 1940s, on their tandem, which they were poised to ride 400 miles from Nottingham to Devon and back. Ted appears relaxed and ready for adventure and Joyce looks fairly chill, too, by her normal standards. But I can’t help wondering what disasters she has envisaged for the journey ahead. The deep dark water they will plunge into while negotiating the paths around Birmingham’s intricate canal network at dusk. The quicksand that might swallow them whole on Weston Super-Mare pleasure beach. The gruesome encounter with one of the huge liminal cats known to stalk Devon’s moorland searching for unsuspecting factory workers on cycling holidays. Nonetheless, they made it there and back safely, and as a result, my dad exists. By extension, it would appear that I do too, unless my life right now, including this newsletter, is all some kind of death dream and, as my dad warned me, I in fact perished back in 2016 in the West Midlands neighbourhood of Digbeth due to wearing a hat that prompted violence from strangers.

People do usually make it there and back safely. That’s something I’ve learned in life, although it’s taken me a while. Like many people, I thought I was invincible when I was young, but I remember always being hugely conscious of the brittle nature of the people I loved. When I was a toddler, being looked after by my mum’s mum, and my parents didn’t arrive back from a party to collect me at the time they’d promised to, I remember - in what now strikes me as a dark and elaborate bit of hypothesising for a four-year-old - always being fully convinced their broken bodies were sitting lifeless in their car seats somewhere on the Nottingham ring road. In my late teens and early 20s, my girlfriend and I always made the other’s landline ring three times to let each other know we’d arrived home safely at the end of the 35-minute car journey between our houses. I suspect such an arrangement happened at my urging: the further surfacing of that part of me that Joyce’s mum passed on to her, which she passed on to my dad and he passed on to me. I’m told, on the whole, that my personality is more reminiscent of Ted: a man so liable to forget to turn the immersion heater off that, as a reminder, his wife made him wear a paper party hat every time he’d switched it on. Like Ted, whose face my mum saw staring back at her the first time she ever looked at me, I am a bit dozy, easily hoodwinked, fond of compost. But I know there’s Joyce in me too, even if it’s more nurture than nature. It’s the small segment of me that’s marginally astonished each time I go on a long car journey and don’t get decapitated by a metal pole that’s come loose from the back of an HGV, every time I go to the doctor’s to get something checked out and don’t discover I’ve got three weeks left to live.

We want to tell ourselves that humans can be sorted into the categories of “optimist” or “pessimist” but I don’t think it’s that simple. I doubt I’m a “glass half full” or “glass half empty” person. If anything, I’m a “can’t remember how much of the glass I’ve drunk, and am unable to verify the state of affairs due to misplacing the glass” person. I’m convinced, at the beginning of every year, despite previous evidence to the contrary, that by December I can learn to play guitar like Bert Jansch, paint like Lee Krasner, garden like Vita Sackville-West, write a minimum of two intricate life-changing novels and read a minimum of 200 others. Yet I’m simultaneously convinced that my new book is going to die on its arse and leave me homeless, and that I’m not going to live past 55. I’m constantly casually, mellowly shrugging off the concerns of those around me when I go out open water swimming alone but I also spend a not insignificant amount of time, awake and asleep, worrying about what the terror of the last moments before drowning might entail. The more I read and live, the more I realise Joyce was correct in believing that the world is a terrifying place, full of danger and incomprehensible levels of evil and pain. But unlike her I am no less aware that it is equally full of kindness, beauty and magic. I have found, like Ted, that focussing on the latter is generally the method that suits me best, even though it sometimes means shutting several blackout blinds in my head and on my laptop.

I haven’t worried about myself much recently. For one thing, there have been too many others ahead of me in the queue. My dad has been chief among them. He’s not been well, in numerous ways. It’s disorientating to witness: he was rarely ill when I was a kid, always seemed the most constitutionally robust of my parents. I know he misses going out into the world and entertaining kids in schools. It makes me sad that nobody is publishing his children’s books any more, that after years of working as, amongst other things, a secondary and primary schoolteacher, he finally got published in the second half of his 40s, and then, after two industrious and fiercely committed decades and dozens of books, the publishing industry essentially turned around and said, “Sorry, you are old now, and we need to make space for some young people instead.” It makes me sad that his paintings aren’t more widely recognised for their brilliance and imagination, and that he hasn’t got the energy to sell them. It makes me sad that I can’t step aside at an event and say “Here’s my dad: he’s going to stand in for me on this one” because he’d no doubt enjoy the attention much more than I do.

“WHERE ARE YOU PARKING?” he asked me before I left for my event in Newark.

“I’m not sure yet. I’ll find somewhere.”

“DON’T PARK IN THE SUPERMARKET. IT’S FULL OF BOY RACERS. TWO PEOPLE GOT RUN OVER THERE RECENTLY. ONE OF THEM DIED.”

“Bloody hell. Ok, I’ll try somewhere else.”

“THE FRONT LEFT TYRE ON YOUR CAR LOOKS BALD.”

“I only had it put on last month. Can you stop worrying just for a second? It’s all ok.”

“OF COURSE I CAN’T. IT’S IN MY NATURE. I USED TO SIT BETWEEN MY MUM AND MY GRANDMA COUPLAND AND THEY’D PLAY DISASTER PING-PONG. ONE OF THEM WOULD SAY ‘MRS MANTWELL FELL DOWN HER STAIRS: THE BOWL OF GRAPES SHE WAS CARRYING SMASHED TO SMITHEREENS AND A SHARD OF GLASS PIERCED HER JUGULAR’ AND THEN THE OTHER WOULD BAT IT BACK WITH ‘OUR MILKMAN’S WIFE’S DEAD NOW’ OR ‘DID YOU HEAR ABOUT THE LITTLE BOY FROM ANNESLEY WOODHOUSE WHO CHOKED TO DEATH ON A FISH BONE?’ YOU DON’T NOT END UP LIKE ME IF YOU’VE LISTENED TO THAT EVERY WEEK FOR THE FIRST SIXTEEN YEARS OF YOUR LIFE.”

If you were to draw me as some weather during these conversations, you’d probably draw the sun, almost totally unobscured by clouds, but with a tired look on its face. That’s the role I play, and has been for years now. Yet, in truth, I don’t mind being worried about; I realise it’s my dad’s way of showing how much he cares about me. But what I realise, more and more, is that, somewhere along the line, our relationship got put on back to front. Unlike my dad, I’m not the one who went up a tree to prune it in the pouring rain in gripless slip-on loafers and fell out of it and broke my spine. Unlike my dad, I’m not the one who had to be cut out of my car by the emergency services after a speeding driver in her 20s rear-ended me at 60+ mph while I was looking for my lost cat. Unlike my dad, I’m not the one who vanished for several hours on a family holiday due to befriending a heroin addict and being keen to discover his life story. Unlike my dad, I go out of my way to avoid potentially incendiary social and political debate with people I’ve just met. But while he talks to me like the man whose son walks constantly through fire out of choice, I reply to him like a person who sees no danger in the world and worries about nothing. We know neither of these people are real, just as I know it’s not real when he says I’m a waste of space. But these are the people we become when we are together and it’s hard to get outside of them, now. He knows he’s being ridiculous but, as an ardent believer in the ridiculous, he’s committed to it for the long haul. You don’t just give yourself a good shake and change the habits of a lifetime. I know that. Nonetheless I will persist in attempting to unJoyce him, to turn him away from the jagged snake-infested ravine he’s often staring at and say, “Ok, but look at the colour in this nice rhododendron behind you, just coming into bloom, and, ooh, is that a baby rabbit I can see below it?”

“DON’T DROP YOUR KEYS,” I can remember him saying to me, when I first started venturing alone into Nottingham, a city whose population was already, by then, well over 600,000. “SOMEONE WILL FIND THEM THEN FIND OUR HOUSE AND BREAK INTO IT.”

My trip to Newark turned out to be lovely. Nobody yelled at me in the street or challenged me to a fight or, for the most part, noticed me. I bought some books from a nice bookshop and a birthday present for my other half from an antique shop. Significantly more than six people came to my event, one of them a childhood friend I hadn’t seen for almost 40 years. The pub afterwards was even better. My mates and I had a whole room to ourselves, the barstaff were cheerful, and nobody got their head kicked in. I enjoyed catching up with people I’ve known for decades and hearing the voices of people I didn’t know filtering through from other parts of the building: voices with accents not unlike my dad’s and my uncle Paul’s and my late granddad Ted’s and Ted’s brother Ken’s, accents like the one I hope I don’t totally lose all vestiges of due to continuing to live 200 miles south west of where I’m from. I walked along the street in my jacket - the poncy one that my dad was worried about - from Newark Town Hall to the Prince Rupert and then from the Prince Rupert to the car, and nobody dragged me into an alley and dug a blade between my ribs. I received a fine, for parking in an ill-defined temporary taxi rank, which ate significantly into the fee I was being paid for the talk, but these things happen. Time has taught me they’re not worth punching yourself in the face over.

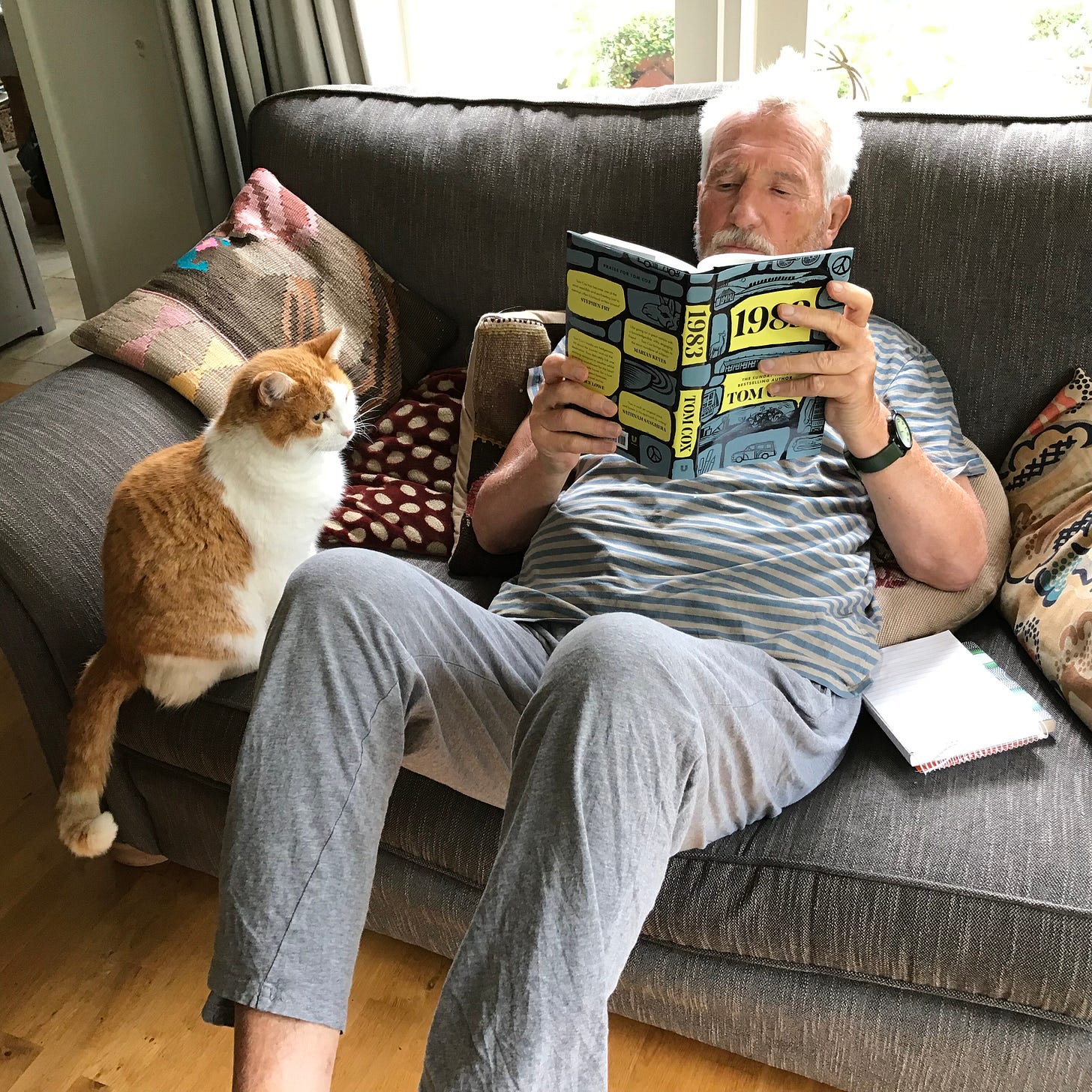

Earlier that day, my dad had told me something surprising: that he’d read my new book and thought it was the best I’d ever written. From day one, he’s been supportive of my writing - he’s always reading and listening more than he likes to let on - but he didn’t comment on my last one and I kind of assumed it didn’t really do it for him. I therefore didn’t have high hopes for his opinion on the follow-up, especially as it features a dad who’s constantly thinking something terrible is about to happen to people around him and telling them not to lose their keys, drown in the bath or get impaled on park railings. But he said he didn’t want it to end.

“CAN YOU WRITE ANOTHER FOR ME THIS WEEK, REALLY QUICKLY? I FEEL BEREFT.”

The day after my event it was the annual Wine Walk in the village where my parents live, and, afterwards, I would hear from my mum that there had been a lot of talk about ducks. People were expressing confusion regarding why there weren’t as many on the river in the centre of the village as there used to be. I would subsequently wish I’d gone on the wine walk. It sounded like fun, and I had generally enjoyed being back in Nottinghamshire, as I tend to more than ever these days. It had been a difficult choice on Saturday morning, but I’d opted not to stay an extra day. I missed my house and its inhabitants. Plus I was due to meet my pal Rob in Derby on the way home for a record-hunting session. So, slightly reluctantly, I’d said goodbye, got into the car and pulled slowly out of the driveway, feeling more than a tad bittersweet. When your parents are in their mid-70s and you live five hours away from them you’re never sure how many more weekends like this you’re going to get. As I exited the drive, my dad, as if remembering something vitally important, ran towards the car, gesturing frantically at me to wind down the driver’s side window.

“TOM!” he said.

“Are you ok?” I asked.

“YES, WELL NOT REALLY, BECAUSE I’M 75, BUT THERE’S SOMETHING I FORGOT TO SAY.”

“What’s that?”

“WATCH OUT FOR FUCKWITS AND LOONIES.”

So, like always, I made sure I did and, thanks to that, once again I got home safely and nothing terrible happened.

It’s now just over three weeks until the release of my latest novel. You can pre-order it - and assist its safe passage into the world - with free worldwide delivery here. My previous novel Villager can be ordered in the same way here. My third novel, meanwhile, is currently funding here.

My dad sometimes sells some of his original artwork here.

You pay such attention to people, and animals, and all things. Thank goodness you are a writer.

Mum and I used to read aloud to each other, until she died nearly 5 years ago. I was re-reading some Margaret Atwood and wishing I could read it aloud to her when my phone buzzed, and I checked it and found this. I may just read it aloud into the Void and hope it connects with some of her residual atoms.