The True Story Of How Julian Cope Licked My Entire Face And Hypnotised Me Into An Occult Life On The Margins Of Society

A lot of people ask me why I am the way I am, so, after many years of holding back, I thought it was time to come clean. The truth is, it all dates back to the day in summer 1994 in the Nottingham branch of Virgin Megastore when the musician Julian Cope - who, it transpired, had been stalking me all over the city from a furtive distance on his hands and knees for several days - licked every bit of my face, coating it in his mystical saliva.

I was freshly 19 at the time, and, after a rule-abiding childhood, had up to that point sleepwalked through an uninteresting and conventional adolescence, playing football and joining my peers in their herdlike dancing to the popular hits of the day in the city’s nightclubs at weekends, while largely devoting weekdays to my faltering attempts to get my new car cleaning business off the ground.

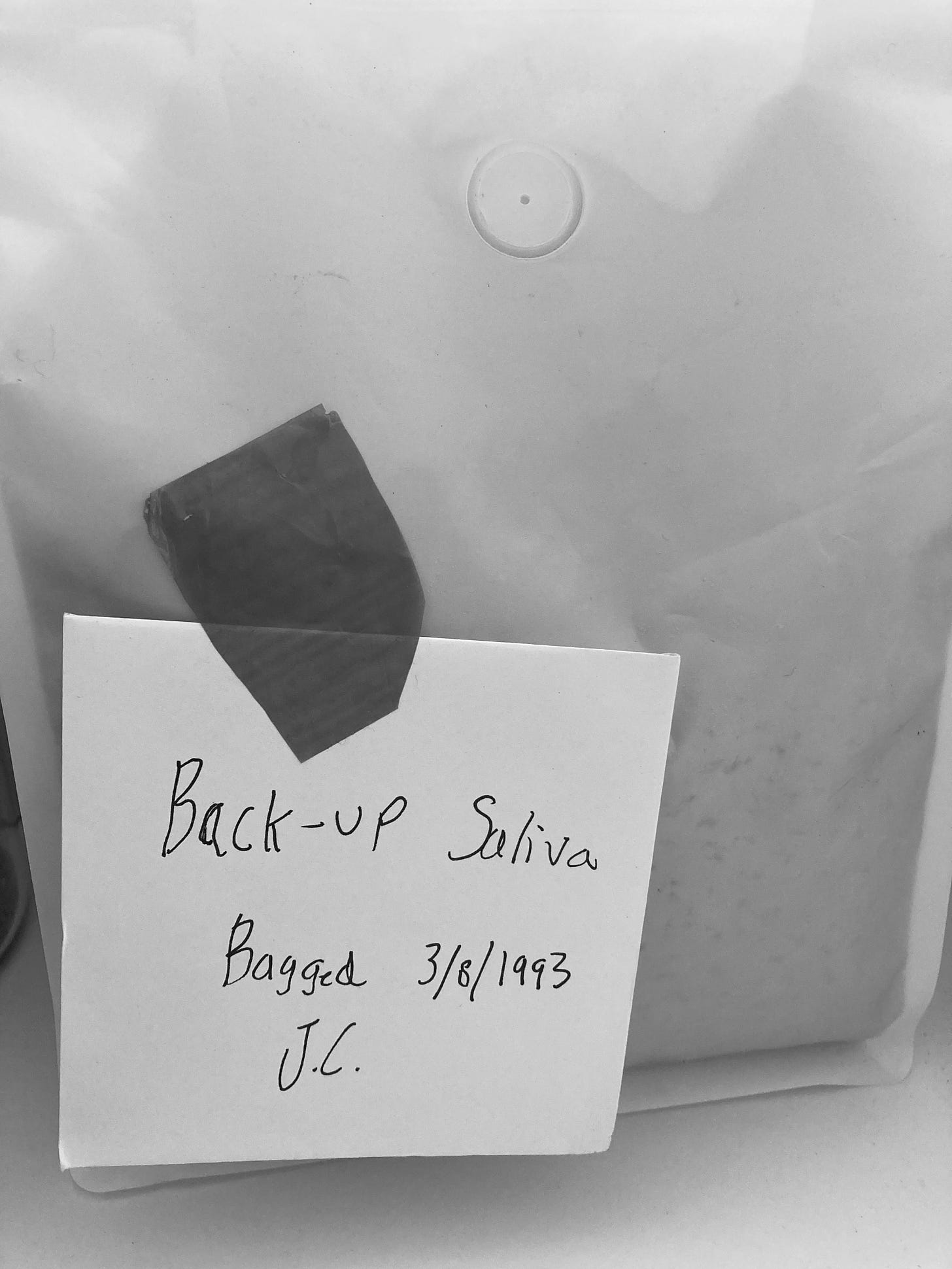

I remembered Julian from seeing him on TV when I was small and he could not have been more lovely when he tracked me down, possessing none of the aloofness and self-importance I’d been led to expect from famous people. He asked me what there was to do for fun in Nottingham. I told him that I had heard Laser Quest was cool, although couldn’t confirm it firsthand, and Julian asked me if I knew that in 1597 the Devil had come to my home city, disguising himself alternately as a newt and a cockerel, and I laughed shyly and said I didn't. While waiting for what he called “the undercoat” of his spit to dry on my face he signed and personalised a copy of his just-published autobiography, all about his time as frontman of the Teardrop Explodes. After he’d carefully applied the all-important top coat, we said our goodbyes, but just as I was leaving the shop and emerging back into the bright sunlight of Wheeler Gate, Julian grabbed my arm. “Hold on!” he said, handing me a white bag, full of clear liquid, around the exact size of my face itself. “You probably won’t need it, but… just in case.”

I noticed myself alter quite a lot in the subsequent days. I was still a teenager, which means being in a constant dramatic state of change, so I thought little of it at the time. But looking back, I now realise the signs were already there, and began from that very afternoon in Virgin Megastore. Below, for example, is a photo of me with my nan, taken only two days after I got slobbered on by the legend who sang ‘World Shut Your Mouth’ and ‘Reward’. I know hair grows more in the summer, but the difference in me seems a little eerie, looking again now. It’s also clear my limbs have become abruptly gangly in a freakish way and I appear notably disturbed by their new length. I love how happy my nan looks, which is almost certainly because the two of us had been to see Hawkwind in concert the night before then managed to sneak backstage, where, after what she claimed was three lagers but I knew for a fact was closer to seven, my nan, still buzzing from the intensity of the moshpit, had coyly swapped landline numbers with the group’s lead guitarist.

That same week, I had visited Nottingham’s best record shop, Selectadisc with the lame handful of albums I owned, swapping them for first pressings of Scott Walker’s ‘Scott 4’ LP, all of the Teardrops and Cope solo records, 1969’s ‘Kingdom Come’ by the Neo-neanderthal metal band Sir Lord Baltimore and various other LPs, mostly made between 1968 and 1971 by Germans or featuring songs with ‘witch’, ‘horse’, ‘woman’, ‘levitation’ or ‘druid’ in the title. It was also around this time that I announced to my family that I would be quitting my job, leaving home and relocating to the United Kingdom’s South West Peninsula.

“You ridiculous streak of piss,” my dad said. “Do you actually even know anyone down there?”

“I know the boulders and the moss and the rain,” I said. “And that is, and shall ever be, enough.”

“But what exactly are you intending to survive on?” my mum asked. “I’ve seen your latest bank statement. It said you were overdrawn by £74.13. And you still owe me for last month’s board and that hair-calming shampoo.”

“Chill there, earth mother,” I replied. “I will survive on trust and pay you back in vibes, over time, with interest.”

I will not claim that the ensuing few years were a walk in the park. My beds were a succession of old pipes, derelict cattle sheds and tin mines. I meditated in trees whose roots wiggled around in the spores of the plague-ridden medieval dead. I stole clothes from the washing lines of lawyers, bank managers and brand executives. I begged and busked enough money for a little extra non-foraged food, and, one thrilling day in 1998, to purchase a first edition hardback of Julian’s pre-Millennial odyssey through megalithic Britain, The Modern Antiquarian. I was often mistaken for a man twice my age. Largely due to all the soil and dead leaves.

Wherever I went where there were houses, I was sure to find an expensive unlocked kitchen and steal some radishes from it. They’d always been my favourite food, and I would never forget the fact that I’d had them for lunch on that magical day when I’d met Julian.

As I walked the moors and coastal paths of the region and danced naked in the full moonlight, protected by its ancient standing stones, I never felt in doubt of the life choice I’d made, which in fact felt nothing like a choice at all, more like holding gently but firmly to an invisible thread that I knew would eventually tug me along to the righteous place, or rather all the many many righteous places. I was flying in the face of fashion, seemed to have a will of my own. In fact, the only genuinely distressing occasion was the one when I had strayed far from familiar territory to stay a few nights inside Hetty Pegler’s Tump, a neolithic chambered burial mound in Gloucestershire, and, while I was out walking the ridge and gossiping with the ghosts of three sexually uninhibited sisters from the Bronze Age, Cotswold vandals broke in and stole some radishes and my bag of reserve saliva, possibly mistaking it for turps. A few months later, when autumn’s first leaves were falling, having experienced disturbing unbidden fantasies about owning a pair of bright orange Nike trainers and stopped myself just in the nick of time as I began to write the opening words of an application for a job with the Devon And Cornwall Police, I set off on the long walk north east, over the chalk downlands, knowing there was only one thing I must do. I hadn’t needed to call ahead. Julian was waiting for me when I arrived, his tongue already pre-moistened and lolling. He complimented me on my roomy sackcloth tunic and I told him I was wearing it in tribute to the not dissimilar garment he’d donned five years ago during his insurrectionary performance of ‘I Gotta Walk’ on Top Of The Pops. I handed him three plump radishes, which I had grown for him specially in the gravel outside an abandoned pumphouse where I’d been lodging with a water goblin who’d taken pity on me.

A report of sorts on the afternoon that followed could be read in the October 15th 1999 edition of The Guardian newspaper, but it scarcely touched on the real story. In the strapline, my editor called Julian a “New Age mystic”, when as anyone knows who’s met him, let alone been gobbed on by him, he’s a whole galaxy more interesting than that. This “reputable” newspaper also edited out the bit where Julian covered me bellybutton to forehead in a conscientious triple varnish of saliva and the two of us used a Ouija board to summon the ghost of the 18th Century antiquarian and stone circle enthusiast William Stukeley. “Here you go,” Julian said, as I left, handing me four more bags of his optimistic occult water. “That should see you right for a good quarter of a century.”

Of course, I am now old enough to have met enough people to realise I am far from The Chosen One, when it comes to Cope’s spit. He’s licked a fuckload of people over the years. What’s interesting is that the effects of his licking are often highly eclectic but all very clearly beneficial to the lickee. In 2014, the comedian Stewart Lee (pictured below) met Cope not far from Cope’s home, at Avebury in Wiltshire, and spent the following seven months living as a muntjac deer. Lee was already a master at his craft before that but it’s obvious that, since his spell as a hoofed ruminant and subsequent return to human form, his timing has become that little bit sharper, his observational voice that bit more unique.

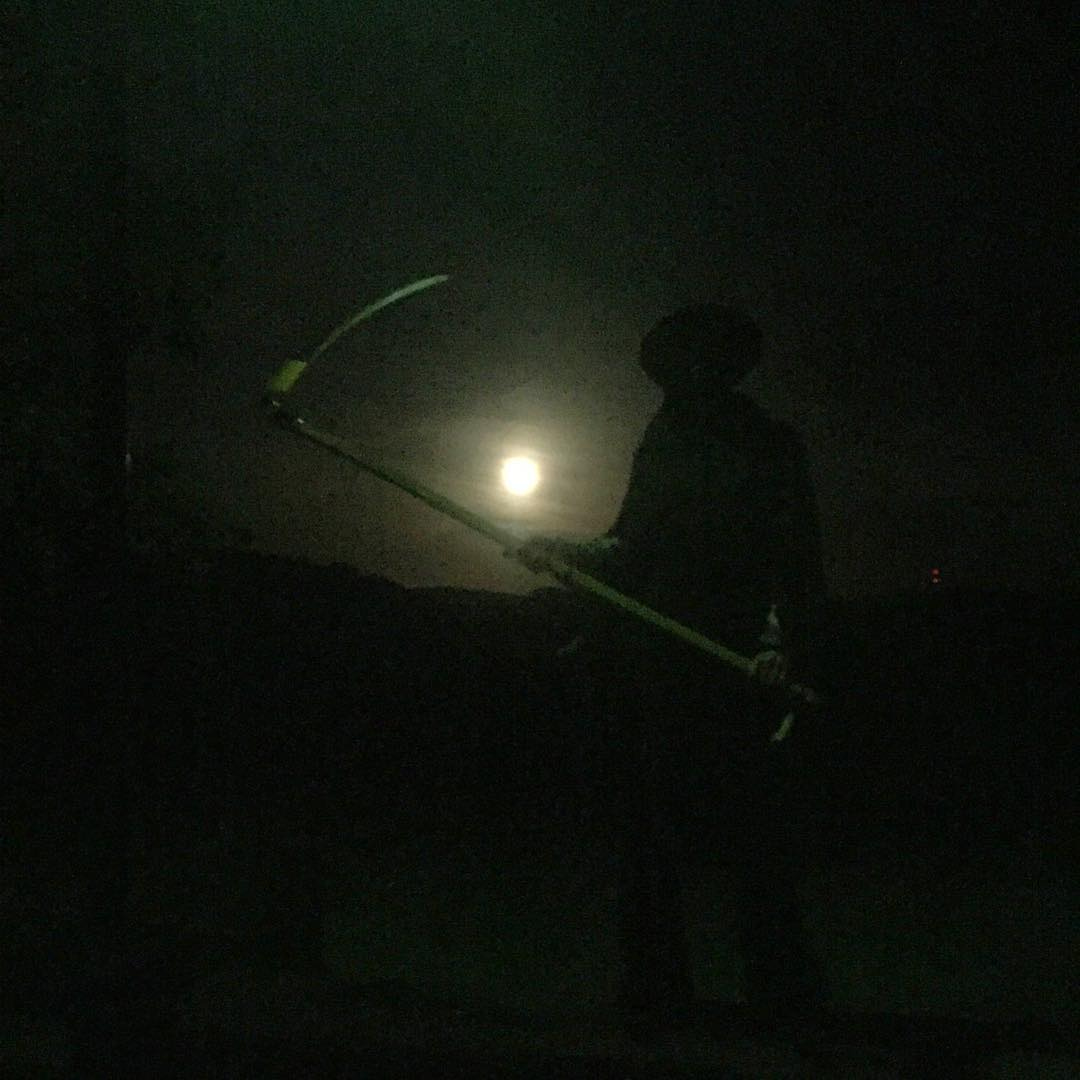

The novelist Rose Tremain described Cope’s spit to me “as more of a kind of lacquer: one that will reliably comfort me at night and make me know I am safely at home in my universe”. My friend Emma, who works as a coastguard, recalls noticing Cope “crawling along the beach behind me, dressed only in a loin cloth” just east of Sidmouth in 1996 and the feeling she had of “instinctively knowing something deeply special was going to happen and I was about to become more inherently me.” In my case, the spit casts its spell in numerous ways: an insatiable need to wander up hills, explore old buildings and commit ostensibly pointless rural acts of trespass. Being on the verge of some conventional notion of success and repeatedly turning away from it to focus on something niche, stubborn and commercially self-harming such as writing psychedelic animist books aimed at a core audience of nine people. Abruptly coming to full consciousness and finding myself far from home under a waxing gibbous moon, dressed in a cape and wielding an Edwardian scythe. Hosting philosophical seminars for curious sheep in the atriums of abandoned factories. Would none of this be a feature of my life, if I had never been spat on that fateful day almost thirty years ago? It is hard to say.

As I write this, I can’t help noticing the date, and its possible significance. I see that my supply compartment is near empty, and, as I do, Julian’s words from that last time I saw him, in 1999 - “That should see you right for a good quarter of a century…” - echo in my head. I am sure magic spit is not an exact science. Do I worry about what the me who no longer feels the effects of Julian Cope’s divine water might become? Well, naturally. Despite being a far less diffident person than I was when he first tracked me down all those years ago, am I still a bit too shy to get in touch and ask for a second top up? Probably. But it also could be said that, in some ways, I have long since lost track of where I end and Julian Cope’s spit begins. When I published my first novel, I sent it to Julian and his wonderful wife Dorian. Dorian wrote me a kind message about it, which my publishers trimmed and used as a quote: “A relatable and compelling read… anyone would love it.” What most people don’t know is that the bit they didn’t use was where she had added: “Of course the real reason it’s good is because of Julian’s spit. In fact, it might be the best book Julian’s spit has written since Rose Tremain’s Music And Silence or that fab memoir Stewart Lee published a few years back.”

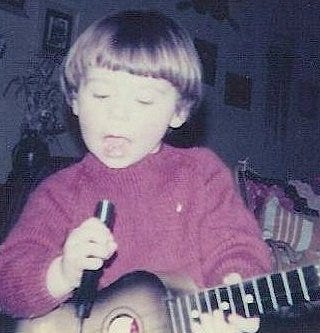

Perhaps, though, there’s an argument that Julian’s saliva has not just anointed me but trained me in readiness for the times I might no longer feel its benefit. If not, I try to keep the faith, as I see my final satchel of expectorate dwindle. In times of worry I often focus on a moment during that evening near to the Millennium’s final curtain in the Cope household. We were up in Julian’s music room and I was basking in renewed appreciation of just how sweet and fragrant his saliva was when freshly applied from the source. I asked him something that had been on my mind, which was the question of how he found me and decided that I, of all people, was the one whose face he wanted to lick that week. I was surprised by his answer. “I’ve always been quite random with these things,” he began. “Maybe I felt you could use a little help. Also I saw you years before, bashing that little guitar, and singing one of my songs. ‘Treason’, maybe? Or perhaps ‘Bouncing Babies’? I can’t remember. You were five and I was on drugs. Anyway, it had a kind of psychedelic punk energy. Especially the bit at the end when you vomited down your pyjamas, that specific ‘fuck off’ energy you had when you did it.”

“But what do you mean, you “saw’ me?” I asked. “You must have been super-busy at that time. You were touring the west coast of America, getting together with Dorian, preparing for a change of direction with the ‘Wilder’ LP. You were a full-on rock star at that point, Tamworth’s answer to Jim Morrison. I was a tiny kid from a non-musical and non-famous family, living between Nottingham and Sheffield, next-door-but-three to a colliery.”

“Oh, don’t worry,” he said. “You never need to worry. I see everything.”

You expect me to believe someone would have radishes for lunch?

"I was flying in the face of fashion, seemed to have a will of my own."

*bows down with respect* 👌🏻